Fashion Week will be with us for months. The Milan show starts out low key by featuring the men. Even on the runway, menswear is far more restrained than the over-the-top experimentation that is typical at the women’s shows. Like each of the big shows, however, some of the designers provide more than a glimpse of next year’s styles; instead, they project a vision of what society could become. What’s interesting about the Milan show this winter is that apparently the future is going to look a lot like the 19th century.

Welcome to the Congress of Berlin. I’d say that aristocrats never looked so good, except that looking good is one of the few things that aristocrats actually do. Here we have fashion models and–are you ready for a bold, even stunning innovation?–movie actors dressed in Prada’s costumes. Gary Oldman leads the procession, as if having a real celebrity somehow lent some cachet to the historical fantasy. The substitution of actor for model makes sense, in a way, as celebrities as a class are the late modern world’s aristocrats, and have the morals to prove it.

Bourgeois morality would not merit a sneer in this crowd, which looks like a melange of grand eminences, minor nobles, and retainers, all of them bound by deeply intertwined habits of calculation, deference, hauteur, indebtedness, and entitlement, with perhaps a dose of inbreeding thrown in. Other models stand in the wings like servants let in for the show, while the focus is on Oldman’s rigorous control of his performance as he approaches some unseen ceremonial encounter.

Thus, one class would dominate the public space, legitimized by lavish performance while hoarding the society’s resources behind the scenes. Not quite where the West is today, but not very far from where it was either. The issue is not simply the distribution of wealth upward while making class mobility ever more unlikely, although that is happening, but also a shift in mentalities. When respect for the social contract of democratic society is displaced by neoliberalism’s promotion of harsh inequalities that become permanent advantages, the 21st century will come to look more and more like the 19th.

On the runway, it’s just a fantasy, here for a few days and then forgotten. But it is because the fashion shows are so explicitly aesthetic and so obviously set apart from the practical world that they can at times leap across the barrier between past and future. What results, if we are willing to take the leap, is an act of political imagination. And the potential future is not always one you would discuss in a political science class.

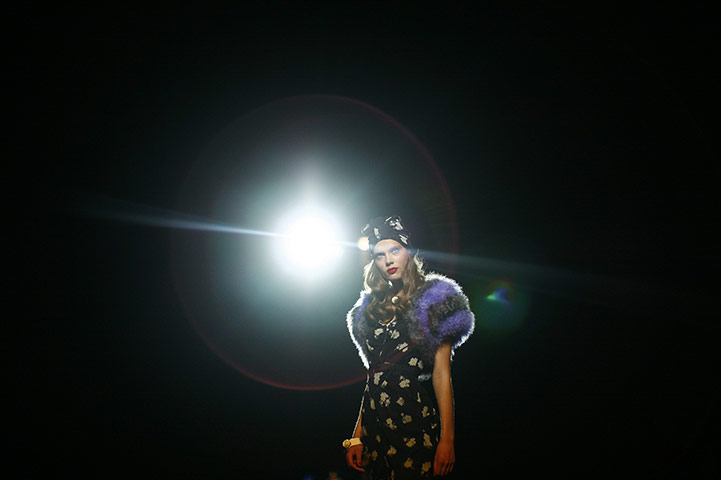

Nor is it entirely imaginative. After looking at fashion or art or photography to discern potential worlds, the next step is to see how those alternatives may already be available in the present. So, if you can’t be an aristocrat, you might think about what you could do to get by in their world.

Jobs may be opening up sooner than we think.

Photographs by Giuseppe Aresu/Associated Press and Erik De Castro/Reuters.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes. The New York Times used the lead photo with this report on the show, which confirms that my read is not off the mark, unfortunately.