Just in case you wondered where the concept of the gnome came from, take a look at this.

This is one of hundreds of photos from The Nightmares Fear Factory in Niagara Falls, Canada. Visitors walk through a former coffin factory, and a camera catches their reactions at the moment that they see a car full of ghosts barreling toward them. Personally, I’d like to send Dick Cheney through, just to see if he is capable of any emotions other than disdain, contempt, arrogance, anger, and all purpose meanness, but that’s just me.

And this is really about the little people. Very ordinary people, enjoying a thoroughly mindless pleasure, so much so that they will pay to be safely scared out of their wits. That’s hardly new, of course, as we know from amusement park rides, horror movies, and Fox News, but here we get to see it.

Which gets us back to the gnomes, and gargoyles, and other mythical creatures, and eventually to Halloween masks. All involve distortions of faces–human, animal, imaginary hybrids–but it may not have been obvious that they could hew close to direct imitation more often that not. Compared to the facial masks that accompany public behavior, which typically stay within the narrow expressive range from blank to pleasant, the fantastical creature appears obviously distorted, deviant, alien, and perhaps dangerous. But they really are among us, part of each of us, expressive beings waiting to be released through surprise, folk festivals, theater, and other forms of play.

Where you don’t see them often is in the public square as we know it, in the broad daylight of the Enlightenment. So it is that the popular media and amusement parks like the Fear Factory can do a good business in letting these other creatures have their day in the–well, not the sun, but at least in the flash of a camera.

Photography is at bottom a form of mimesis, that is, imitation of a given reality. (We don’t say that the photographer creates the thing photographed, only the photo that records the thing, but the artist creates a painting or a poem that need not refer directly to anything outside of itself.) Imitation in the modern era was thought to be inferior to art, and the more “mechanical” the imitation, the farther it was from having artistic value. This did not bode well for photography.

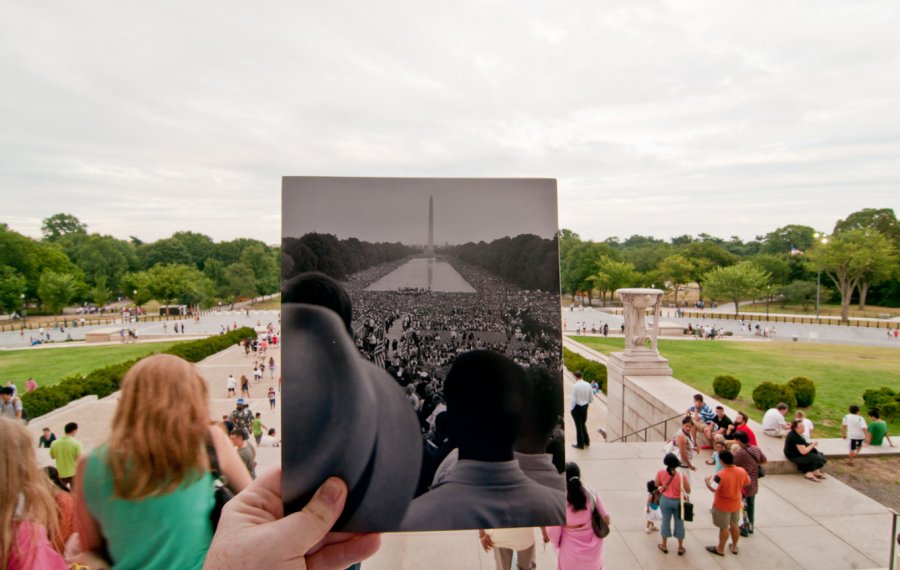

Look at the image above, for example: it probably was taken automatically, without human action, and it merely recorded what actually happened. Of course, it does more than that: the happening lasted less than a second but now is permanent, framed, and otherwise presented for the entertainment and edification of a spectator. And more as well, but that is not the point today. It is enough for now to consider how the fundamental slavishness of the medium to an exterior reality might actually be a clue to how the imagination works.

Imagine that gnomes, gargoyles, and the like came from observing the iconography and physiognomy of human expressiveness, the plasticity of the human face, and our kinship with the uncanny. You could almost think of them as a premodern sociology, one (appropriately) worked out in visual media. (For a different but related example, consider the 71 stone faces at the Cathedral of St. James in Sibinek, Croatia.) In other words, artistic expressiveness in the folk arts need not come from distortion of a basic, blank face, but rather from imitation of actual expressions, which could be enhanced further via formal extension of the tendencies revealed there.

Consider also that the blank face might be more widespread and normative today because of the prevalence of a global camera culture that had its origin in norms of bourgeois deportment. Those tendencies were then inflected toward a uniform visage of pleasantry through visual practices such as advertisements selling happiness, family members saying “cheese,”and so forth all the way down to the smiley button. Which then lead to the mildly transgressive fun to be had in a photo booth or with a camera phone: underground, carnivalesque, like the gnomes.

In other words, the fantastical products of our imaginations are, like gnomes and ghosts, imitations of reality. They come from taking what often is overlooked and making it the basis for further elaboration. No wonder that they then can carry so much other meaning and lead to discovery and transformation, which they do. If that is so, then photography is in fact squarely aligned at the center of the human imagination. It is an medium not merely for recording reality, but for finding a basis for creative imitation and elaboration of human expressiveness.

![Liz-Scott-Jane-Greer-The-Company-She-Keeps[1]](http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Liz-Scott-Jane-Greer-The-Company-She-Keeps1.png)