As a matter of course, we just don’t do gag photos at this blog. After all, we’re providing serious public commentary, right? And we feature many outstanding photographs. As the gag photo often is assumed to be the sure sign of amateurism, you wouldn’t expect to find it among the images of the week.

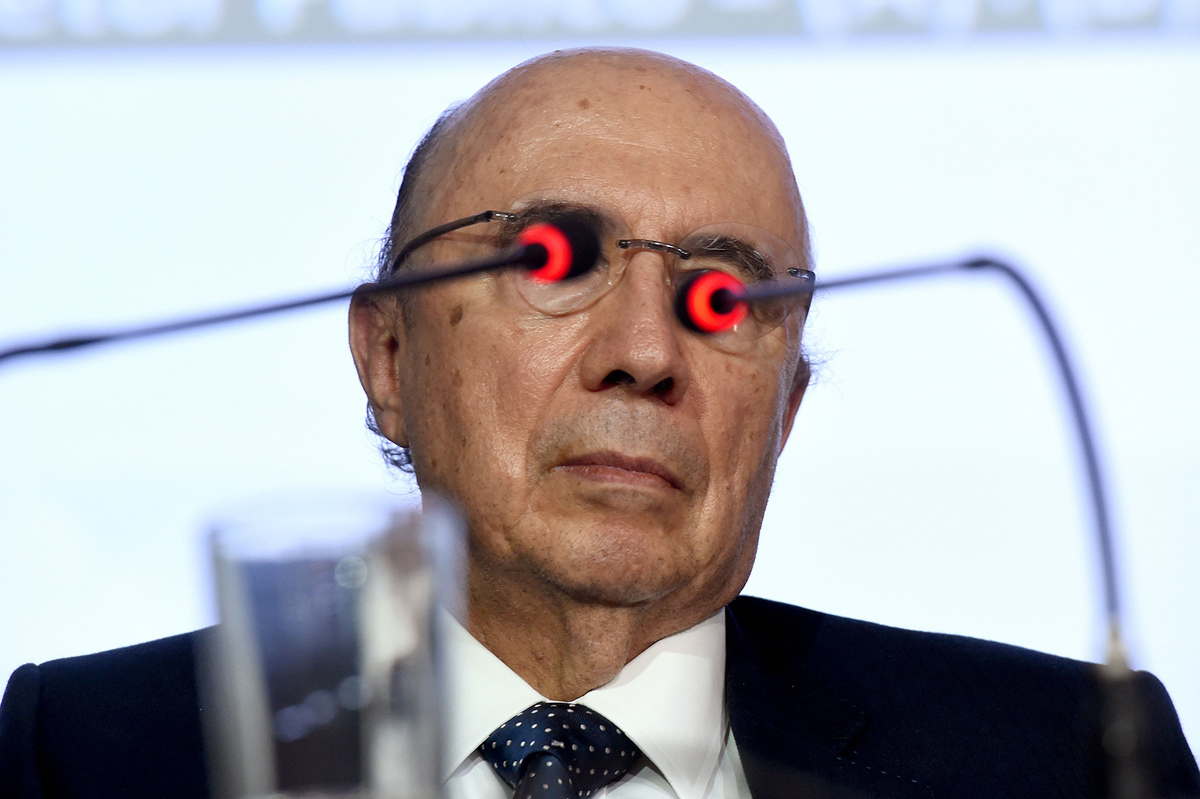

And you’d be wrong. You’d be wrong in the specific case, as with this photograph of Henrique Meirelles, the Finance Minister in Brazil’s interim government, at a press conference in Brasilia. And wrong more generally, as one of the very best professional photographers, Elliott Erwitt, produced dozens of visual jokes very much like the one above. In fact, this image looks like a signature Erwitt photo, but I doubt it’s even an homage.

I was tempted to write that Erwitt “had a weakness for” visual jokes; that’s how conventional discourse does our thinking for us. It wasn’t a weakness, however, but another angle on the human condition. Likewise, is the photograph above really of Henrique Meirelles, who I’ll bet does not have two antennae protruding from orange eyes? If it’s not an image of the person named in the caption, what is it?

One answer might be that it is a portrait of an official. Not a specific official, but an idea or at least a caricature of officialdom. In that respect, it may be closer to the reality of modern finance than the idea it displaces: why continue to believe that decisions are being made primarily by prudent individuals, rather than being pushed one way or another by data flows and the abstractions that accompany them? Does he see the material hardships of ordinary experience, or does he see instead through the optics of financial instruments? Is he one of us, or does he represent the many levels of alienation that stand between ordinary experience and the decisions made at the top of elite institutions?

As that gap grows, it leads to more anger from below. Growing inequity leads to reactions on both the left and the right, and to more demonstrations and other protests, and to violence.

And to more gag photos.

Here the term “gag” may acquire additional meaning, although the Orange County Sheriff’s deputies may be well trained (may be; it’s possible), and the Masked Marauder seems to know the drill.

But is it a gag photo? In one sense, no: the surreal juxtaposition of Halloween mask and riot gear is in the scene, not an optical illusion created by the camera. But in another sense, yes: compared to the other demonstrators at the Trump rally, he probably is featured because he’s got the most unexpected costume, producing an image that most of the time would have to be created by special effects. But in yet another sense, no: it’s not funny. But in another sense, yes: he’s probably wearing the mask to provoke a laugh or at least something edgy enough that it’s on the edge of nervous laughter. So, once again, we might ask, what is it?

One answer is that, similar to the image above, we are not being shown a specific demonstrator but rather an idea or at least a caricature of political unrest today. In any case, one that is closer to the truth than what a more “unmasked” portrait of the individual would provide. The grotesque mask (and hair) seamlessly fitted to the cameo clad bruiser suggests that we are seeing Trump’s alter ego: the surreal forces of unreason and violence that lurk below the surface of his campaign. The many similarities with the police restraining him suggest the alignment or affinity between forces of disruption and those promoting “security” and “order” at the expense of civil society. The fact that he probably is protesting against Trump suggests that the Left can get sucked into the same downward spiral.

Not funny, not funny at all. Makes me want to see something light, even silly. Maybe a dog’s head in place of its owner’s. Just a gag, you know. . . .

Photographs by EVARISTO SA/AFP/Getty Images and Jae C. Hong/Associated Press.

Cross-posted at Reading the Pictures.