The wife of a police sergeant disappears, and stays disappeared. Turns out that she is–or was–his fourth wife, and the third wife had expired in suspicious circumstances, and the cop may have been using police department computers to get information on his (fourth) wife’s friends, and the story gets curiouser and before you know it, he resigns from the force while becoming both a police suspect and the hot story in the Chicago media.

And they say the suburbs are dull.

Even if this guy beats the rap, it’s clear there is much not to like, but that’s his business. My interest in how he has provided a lesson about the visual public sphere. Peterson clearly has adapted quickly and dramatically to the media mob camped outside his house. Here’s where he started:

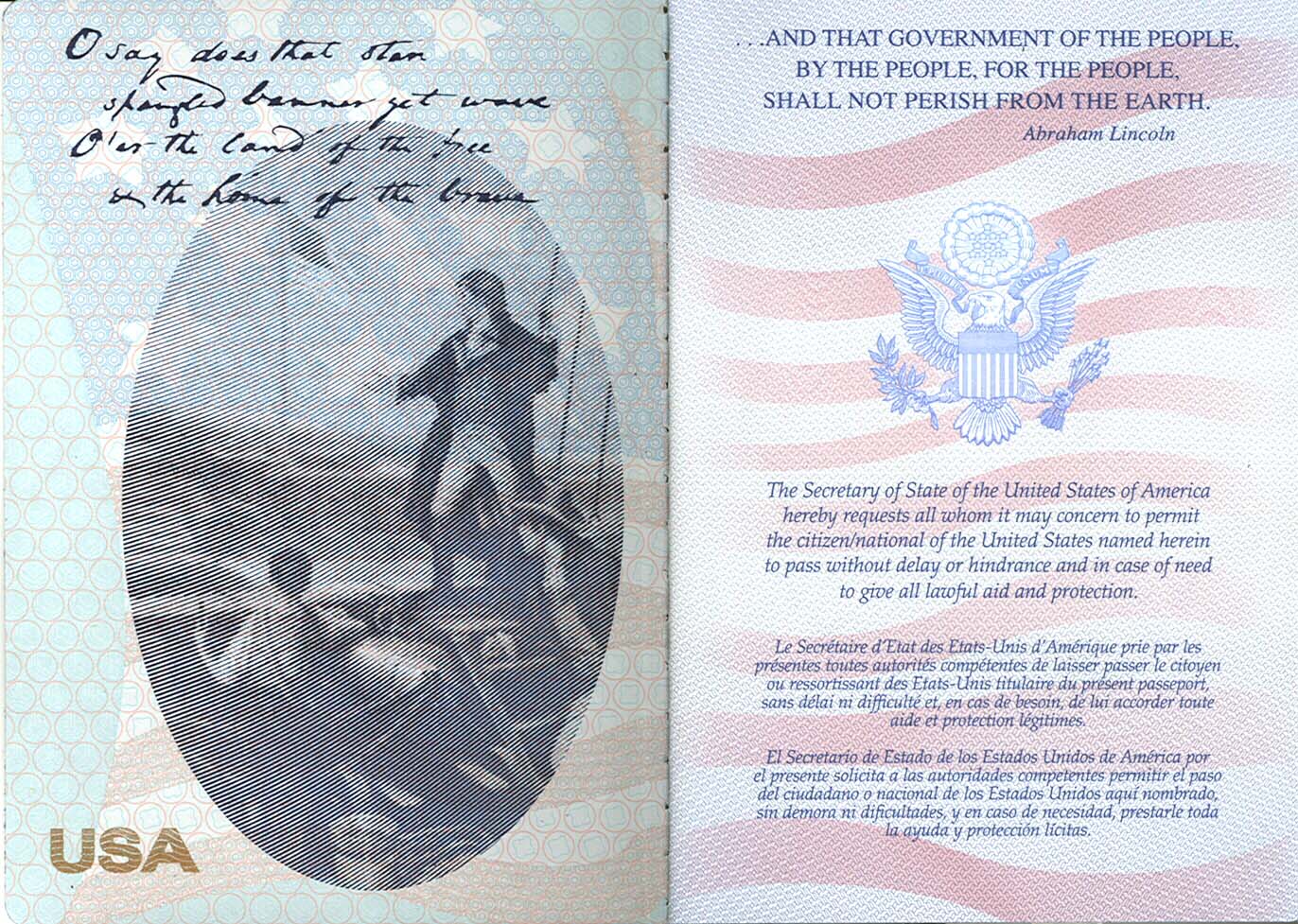

The caption read: “Bolingbrook Police Sgt. Drew Peterson — whose wife, Stacy, has been missing since Sunday — steps outside his home for a few seconds as police investigators search his home Thursday. Asked about whether he was nervous, Peterson told the Tribune, ‘Why should I be nervous? I did nothing wrong.'”

Now it can get chilly in Chicago in November, but you don’t have to cover your face. I thought of doing a separate post on this photo and calling it “American Burqa.” By bundling up against the media gaze, Peterson is challenging our norms of public visibility. Some of us resist the demand to be seen, as when we wear sun glasses inside or ball caps pulled low, but that is always within the range of legitimate withdrawal into a zone of privacy. As Peterson shows, all you have to do is cover the face itself and your display of autonomy is no longer acceptable. No wonder the guy looks guilty as hell. The picture says, “withholding information, hiding something, and a law onto himself.”

It is easy to conclude that this strategy of hiding in the light is not so smart. But don’t conclude that Peterson is not cagey. The jacket and jeans combo, NYPD ball cap, and flag bandanna scream “selected for symbolic value.” He may not be nervous, but he is trying to put some visual spin on a bad situation.

Turns out that he’s also coachable. I’m speculating here, but I’ll bet he got a lawyer and some help on the presentation of self in public. Because this is what we saw more recently:

Whoa! Is that the suspect or his lawyer? Comfortably striding along in middle class attire, he turns his video camera on the press. Instead of denying the norm of public visibility, he ramps it up, creating a hypervisual scene of cameras recording cameras recording cameras. Instead of passively hiding in full view of an unseen camera, he aggressively records the press, thereby bringing them into the picture. Instead of looking isolated and guilty, he declares that he has nothing to hide while the press is unfairly ganging up on him.

He’s catching on, isn’t he? This is what conservative politicians and media flacks have been doing for years: shifting the focus from their actions to the media coverage, which then is denounced as excessive and unfair. You can’t paint Peterson completely with that brush, however, as his brash act has another, more distinguished lineage. This includes Garry Winogrand, a photographer who focused his camera on the technologies of media coverage (see his 1977 book, Public Relations), and, behind him, Walter Benjamin’s argument that photographic artifice depends on hiding the equipment. By exposing the cameras trained on him, Peterson has not only adopted a sophisticated strategy for deflecting the gaze, but also activated a more reflexive awareness of the role of photojournalism in shaping the story.

Even so, I think he still looks guilty as hell. It’s probably the smile. . . .

Chicago Tribune photographs by Antonio Perez (November 1, 2007) and Terrence Antonio James (November28, 2007). Thanks to Elisabeth Ross for reminding me of Winogrand’s work, which was included in her presentation on “Private Eyes and Public Lives” at the recent Northwestern University conference on Visual Democracy.