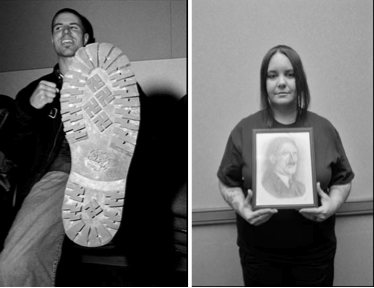

In contrast to the many images of right wing demonstrators disrupting town hall meetings, this photograph of elderly citizens listening to a discussion of national health care appears to be a model of thoughtful deliberation.

They are old, yes, but not incapacitated. Indeed, this is just what an audience is supposed to do at a democratic forum: listen carefully. The individuals here appear by turn skeptical, reflective, and (in the background) critical, and in every case attentive. Isn’t this what everyone should be doing when thinking about the momentous questions of whether and how to reform health care?

Well, yes and no. The problem is that, as a group, the elderly are tilting against reform, despite not being out of synch with the rest of the electorate on other issues. But is that a problem? Obviously not if you oppose reform, but otherwise it is indicative of several ironies within the health care debate and at least one paradox within democracy itself.

Needless to say, all of the elderly have the government health insurance that some of them would deny their fellow citizens. It’s called Medicare and not “the public option” or “socialized medicine” or “government interference in the doctor-patient relationship,” but it’s all of those things–and a good thing, too. And, of course, the vast majority of those who have it like it and assume that they are entitled to it. Nor do many of them know that those politicians and organizations that oppose the current reforms also opposed Medicare. Most tellingly, this group watches more TV news than other voters (something that oddly is often described as being “more informed”), and some of them go so far as to claim that they oppose reform because then don’t want the government involved with Medicare.

A more vexing problem is that, because democracy depends on the secret ballot and aggregated decisions, any voter can behave with a very skewed sense of responsibility. One can vote against government benefits while remaining assured that you will continue to receive government benefits. So it is that Red States that vote against “big government” receive more government money than they spend in taxes. Obviously, if the state’s net take was dependent on the political philosophy it endorsed, voters might think twice about their decisions; but, of course, they don’t have to. Likewise, if those elderly voting against the public option had to give up their public health care, they might think differently, but that’s not an option. This disconnect between political rhetoric and government policy has become second nature to all of us. We accept that politicians can rail against the government while securing government contracts and services for the home district, and that you don’t have to be held personally responsible for your vote.

In other areas of life this would be seen as rank hypocrisy. Imagine saying that everyone in the family has to eat vegetarian, except me; or that everyone in the congregation ought to pledge, except me; or that everyone in the office has to observe the dress code, except me. Whereas in private life we take it for granted that pronouncements and actions should be consistent, democracy seems to make hypocrisy a virtue. What is not readily acknowledged is that this hypocrisy is characteristic not merely of politicians, but of the voters as well.

Paradoxes exist for a reason, and this one probably leads to good outcomes as well. What is needed, at least in the hear term, is more attentiveness and more imagination. Look again at the photograph above. One can see democratic deliberation, and also the frailty and mortality that is the core of our human condition. One can see, in other words, not only a civic habit but also the fundamental purpose of government.

Note also how each of the individuals is in a defensive posture. They are protective of themselves, and understandably so. And keep in mind that none of the press reports defines the elderly in terms of experience or wisdom, but only in terms of the demographic power at the polls. Given the lack of respect typical of a traditional society, they know that they have to mobilize according to shared interests.

What they, and we, must understand is that self interest can only be fully realized by taking care of others. From that perspective, the problem is not that the elderly are in the picture, but that they are solely among themselves. The better understanding will come not by carefully addressing their problems, but by putting those problems in a wider context, one that is at least wide enough to make the high costs of hypocrisy apparent to all.

Photograph by Alex Wong/Getty Images.