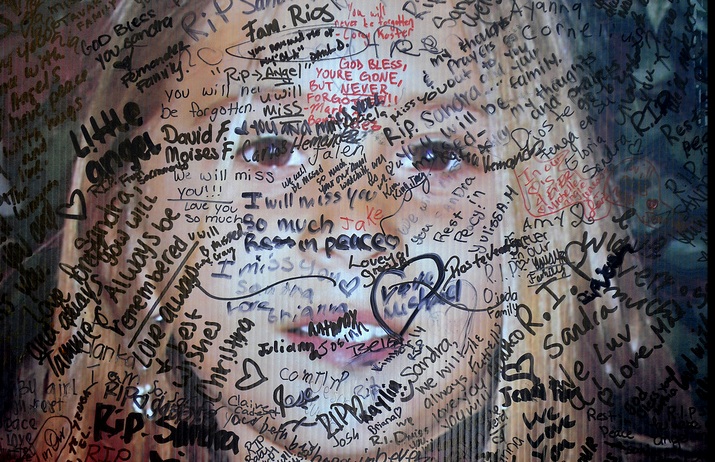

The photograph above is a haunting image of Sandra Cantu, an eight year old girl who was abducted, sexually molested, and brutally murdered, her lifeless body found stuffed inside of a suitcase in an irrigation pond near her home in Tracy, California. The image is part of an eight foot poster that emerged in a spontaneous public memorial outside of the trailer park in which she lived, along with candles, stuffed animals, flowers, balloons, etc. What makes the photograph so evocative is the way in which it underscores the function of the writing on the poster-sized photograph as something of a public shroud that veils the precious and innocent life so tragically cut short, even as it accents the vitality and penetrating demand of her eyes.

There was a time, not so terribly long ago, when post-mortem photographic portraits of loved ones—and especially children—were taken and cherished as private momento mori, reminders of the fragility of human life and of our own mortality. Such images today are considered morbid. Instead, now we remember deceased loved ones by photographs of them taken while they were still alive, and usually such images are the candid snapshots that fill our family photo albums, the nostalgic Kodak moments that seem to be the accoutrements of middle-class, private life. Indeed, it is not rare to attend a private wake in which digital slides shows of such snapshots become the center of attention, as much if not more than the casket or urn. In the photograph of Sandra Cantu, however, the private snapshot has been refashioned as a public image, albeit with a significant difference.

The snapshot in a private wake functions to invoke and reinforce the identification between the deceased and the bereaved in very personal terms. Here, however, the point of identification is more public than personal—more a demand for protection (and perhaps a public reflection on that demand) than a simple reminder of innocence and happier times—and as such it invites our consideration as a symbol of our civic and political relationships. Hence, what was once a candid snapshot has been reproduced as a larger than life portrait and fixed in a very public setting, its political voice announced and secured. But there is more, for note too how the collective public signature weaves a scrim that separates the viewer from the girl, almost as if to protect her from the voyeurs’ gaze. And yet, as in this case, such protection can only go so far. The photograph thus takes on the quality of a civic momento mori, an allegorical reminder of both our civic responsibilities as well as how fragile public efforts to protect one another—and especially our children—can be.

Photo Credit: Michael Mccollum/AP