Photo Credit: Susan Walsh/AP

The Art of Defiance

Guest Correspondent: Bryan Thomas Walsh

It is campaign season again, that phase in the cycle of American political culture when candidates from both political parties stage over-the-top displays of patriotic grandeur: they salute flags, attend baseball games, eat hotdogs at state fairs or in corner diners, shake hands with the masses, and enact an array of additional public performances that are believed to enhance one’s public image. We are, in other words, moving from the circus of the Republican primaries to the carnival of the American presidential campaign.

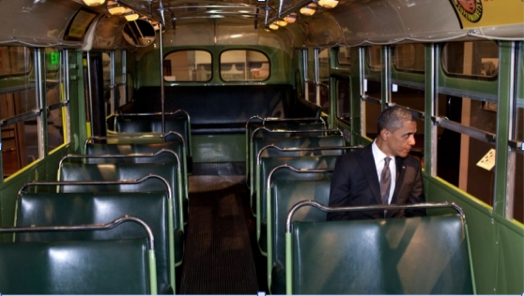

Given the ubiquity of hyperbolic theatrics that are so conventional to presidential campaigns, one might be taken aback by the above image. Taken just two weeks ago in Dearborn, Michigan by White House photographer, Pete Souza, the image captures President Barack Obama sitting solemnly inside of an empty, old-fashioned bus, looking intently out of the window and beyond the frame. At a glance, this is a puzzling image. Removed from the typical whirlwind of photographers, news reporters, and law enforcement, the President is seen here in a rare moment of solitude and private reflection. In many ways, the scene is neither spectacular nor conventional. It is only after reading the caption that we discover that the President is sitting in the very same bus where, almost 60 years prior, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man, thereby igniting the Montgomery Bus Boycott and reenergizing the Civil Rights Movement.

Of course, given the superficiality that characterizes contemporary campaign spectacles, it is not hard for viewers to read this image as a mere “photo-op.” Accordingly, viewers are invited to read the reference to Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement as an example of the President pandering to his liberal constituency and black voters in particular. Alternately, viewers can read this image as an attempt to frame the “first among equals” as an ordinary guy on his way to work, an image that Republican candidate Mitt Romney persistently fails to achieve. Michael Shaw at the BagNews argues that the image is an example of political “muscle-flexing,” where a crafty campaign strategy aimed at renewing the public’s opinions about the President parades around as a “candid photo involving a moment of deep reflection.”

While it is understandable for viewers to interpret this image within a cynical register, there remains something incredibly evocative and moving about the image. Indeed, the image emits an aura of authenticity – that is, it seems to capture a sincere and poignant moment where the President feels the gravity of the past and its bearing on the present or, more specifically, the role of Rosa Parks’ resistance to segregation and its relationship to the reality of Obama’s presidency. Rather than repeating the cliché and empty theatrics that saturate the campaign season, this image captures the President coming to terms with the fundamental fact that his presidency was made possible by those “second-class citizens” who defied a racist political system and executed acts of civil disobedience in hopes of realizing a more fair and equitable future for people of color. In short, the photograph serves as a history lesson insofar as it calls on viewers to recognize the role of civil rights struggles in having real effects (however oblique) on the vitality of present-day progressive politics.

But it is not only a history lesson; it is also lesson about social change. Seen here a year after the Montgomery Boycotts and the subsequent reintegration of the transportation system, Rosa Parks sits earnestly at the front of the bus alongside a visibly white passenger. The parallels between the image of Rosa Parks and the image of President Obama are striking: not only do both Parks and Obama occupy a space that was historically closed-off to blacks, but Obama unwittingly imitates the firm resolve suggested by Parks’ gaze. While the apparition of Rosa Parks reminds viewers that the Civil Rights Movement paved the way for a black man to serve as the President of the United States, she also reminds us that the vitality of contemporary democratic culture depends on the public dissent and civil disobedience of individuals and communities. One can only hope that Obama will take a hint from Rosa Parks – namely, that democratic promises are not always realized through compromises and civility; they emerge in the wake of overt and orchestrated political defiance.

Photo Credit: Pete Souza/White House; UPI/Library of Congress

Bryan Thomas Walsh is a Ph.d student of rhetoric and public culture in the Department of Communication and Culture, Indiana University. Correspondence should be sent to btwalsh@umail.iu.edu.

The Modern Condition

It has been a full year since Japan was overwhelmed by an earthquake and tsunami and like clockwork the major media slideshows have responded with a series of “then” and “now” photographs (e.g., here, here, and here) marking the slow but steady progress of an advanced society—in many regards a society much like our own—as it returns from utter devastation to a bustling, self-sustaining economy. It has not fully returned, but it is on the path to recovery and the comparisons surely invite our sympathy and admiration. In January we saw a similar set of visual comparisons (e.g., here) on the one year anniversary of the earthquake in Haiti, but with this difference: while it appears that Haiti has recovered some from the disaster, it continues to be an impovrished, utterly dependent, “other world” nation that invites neither our identification nor our sympathy so much as our pity.

The differences between Japan and Haiti are signified in a multiplicity of ways, not least in how the devastation in Japan seems to have been largely structural, effecting roads, bridges, buildings, and other forms of physical property, whereas the devastation in Haiti has been more social and economic, exacerbating an already starving, unemployed, uneducated, and generally impecunious population. The above photograph is telling in this regard. It is a photograph of lost photographs collected in a local school gymnasium in Natori, Japan, waiting for their owners to seek them out and recover them. Some are quite obviously old, perhaps even antique, and thus mark a sense of historical continuity that spans generations and thus mitigates the impact of the more recent and comparatively minor “then”/”now” dialectic that commemorates no more than a span of twelve months. But perhaps more importantly, these photographs are obviously cherished items, their value signified not just by the fact that they are framed and were thus objects of display in the home, but because they were patiently and laboriously culled from the detritus left behind by the earthquake and tsunami and collected with the hope that they would be found by their respective owners.

Collection centers such as the one above can be found throughout Japan, and some are down right enormous as in the photograph below which identifies a site that contains more than 250,000 photographs . And the point should be clear: more than lost property, these lost photographs are quite clearly significant momento mori, cultural artifacts that identify the society that takes them and preserves them as a modern, technologically sophisticated, bourgeois civilization (not that one has to be bourgeois to take and keep photographs, and the practice of snapshot photography cuts across all economic classes where it is an established cultural convention, but it rarely occurs in societies that lack an established middle-class).

And so it is that when we turn to retrospectives of Haiti we don’t find the preservation of family photographs at all. That is not to say that photographs are unimportant, but as with the image below, they signify not an established, modern cultural practice, but rather a modernist intervention of sorts.

Here a Haitian woman shows a photograph of herself as she was pulled from the rubble of a house that had fallen upon her. The photograph was taken by an AP photographer and then given to her. It is clear that she values it, but importantly it is more a curiosity—or perhaps a marker of humanitarian aid—than a conventional cultural artifact, and as such it designates the society in which she lives as pre-technological if not in fact premodern. One finds a similar curiosity and intrigue displayed and accented in photographs that show Haitian children (here and here) being introduced to cameras and photography by the Art in All of Us project.

The simple point would be to notice how two societies are distinguished by their attitudes towards photographic technology: one modern and mature, the other premodern and either immature or innocent, but in any case defined as childlike and needy. But perhaps more important is the way in which the photographs above function in each instance as media that model social relations, inviting us to see and be seen as members of a social order driven by the differences that simultaneously separate us and connect us. That, perhaps more than anything, defines the modern condition.

Photo Credits: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images; Toru Hanai/Reuters; Dieu Nalio Chery/AP Photo

The Silent Erasure of Executive Order 9066

Tule Lake, Minadoka, Heart Mountain, Grenada, Topaz, Rohwer, Jerome, Gila River, Poston, Manzanar: their names should be etched on our national consciousness as a reminder of how quickly fear can blind us to the “better angels of our nature” and activate the dark side of our democratic sensibilities. But of course they are not; indeed, in all but a few cases the names are barely recognizable. This week marks the 70th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, President Franklin Roosevelt’s ignominious decision to “relocate” some 110,000 Japanese-Americans—over two thirds of whom were U.S. citizens—in the ten internment camps listed above and scattered throughout the western portion of the nation. Roosevelt signed the order on February 19, 1942, and that the national media has chosen not to acknowledge the occasion of its anniversary only compounds the original tragedy by contributing to the erasure of its memory.

The photograph above was taken twelve years ago at Manzanar, a relocation camp located five miles south of Independence, California—the irony of its name should not escape us—and home to over 10,000 interned Japanese-American residents. The rusted and bent barbed wire that frames the landscape, emphasizing the wide open spaces and the big sky, is at home in the American west where it was a tool used to establish the boundaries of land ownership in an expansive frontier, and to contain and control cattle or other livestock. Ordinarily such a framing of the landscape would not warrant a second look as perhaps anything more than a photographer’s affected representation of the relationship between nature and civilization. But here, of course, the barbed wire is not a tool of civilization but a weapon of war, its purpose to imprison a race of people whose only crime was that they didn’t quite look like “us” and whose ethnicity identified them with a country that was at war with the United States.

When located in relationship to its proximate political history the focus invites us to shift our attention from the background to the foreground, from the majesty of the sky and the distant mountains to the violent protrusions of the barbs, from now to then. While all else seems to have been erased—the stables that were initially used to house humans, the eight guard towers that surrounded the compound and provided twenty-four hour surveillance, and indeed the compound itself—the barbs, cast almost but not quite in silhouette, linger as a twisted reminder of our own violent and unjust past, of what once was and risks being again if only because it risks being no more in our collective, public memory.

Photo Credit: Getty Images North America

Manzanar is now a national historical site maintained by the National Park Service.

The Good War in Reverse

The point of comparison is apparent. The visual quotation is to what is arguably one of, if not the, most famous, recognizable, and reproduced photographs in all the world. And more, it is the photograph most often pointed to as the icon of “the good war,” a total war fought against unregenerate, totalitarian evil in the name of freedom and democracy. And what made that photograph taken in February, 1945 so incredibly powerful was the way in which it transcribed and coordinated commitments to egalitarianism, an embodied sense of nationalism, and a civic republican ethos within a single image. What makes the photograph above so distinct—and in its own way quite important—is how, despite its obvious gesture to the original, it resists or erases everyone of the original three transcriptions.

The Iwo Jima photograph depicts the war effort as essentially egalitarian. We see six men, all wearing identical uniforms, with no indication of rank, engaged in common labor for a common goal. They are a working class equal to the task because they are working equal alongside one another, no one straining more than another, no one more at risk than another. The sacrifice is thus collective, the individual subordinated to the common good. In its way, the egalitarianism of the photograph modeled the egalitarianism of the overall war effort, not just on the battle front, but on the home front as well, where rationing, Victory gardens, and the purchase of war bonds were the order of the day. But in the photograph above, shot at Camp David in the Helmand province of Afghanistan, there is no egalitarianism because there are no equals. Instead of a collective effort to raise the flag we have a single individual struggling against the wind to put the standard in place. The effort and the sacrifice are solitary. He alone does the job. And if the photograph gestures to the original icon of the “good war,” where the sacrifice was egalitarian, it also points here by implication to a war fought by individuals rather than by the nation as a whole. Perhaps that is why he seems to struggle so hard and why it is not altogether clear that he will overcome the force that opposes him.

References to the nation here are not incidental, for in the iconic image the commitment to egalitarianism was inflected by a pronounced appeal to nationalism. It is notable that captions for the original photograph emphasized “Old Glory” or “the flag,” underscoring the symbolic significance of the standard being raised. As one of the original flag raisers commented years later, “You think of that pipe. If it was being put in the ground for any other reason … Just because there was a flag on it, that made the difference.” The caption for the above photograph, however, virtually ignores the national significance of the flag itself, as it notes that “U.S. Army SPC Jeremy Stocks … restores a flagpole back in place after the flagpole fell in a night sandstorm (emphasis added).” The flag is there, to be sure, but it is reduced in significance to the pole itself; the banner could symbolize anything as far as the caption is concerned—a regiment for example—and it would not seem to matter to the task at hand. But there is more, for you will no doubt recall that in the original photograph the flag raisers were turned away from the camera, leaving “Old Glory” as the face of the image. Indeed, it was not insignificant in this regard that the flag raisers were initially anonymous and thus capable of standing in for an anonymous national public. But here the flag raiser’s face is fully recognizable and he even has a name. The opportunity for collective or national identification is thus doubly removed.

Appeals to nationalism typically operate in an heroic register, and in the U.S. this often manifests itself in a civic republican style that emphasizes (among other things) monumental sacrifices by ordinary people. The Iwo Jima photograph manifests this larger than life heroism with its monumental outline and sculptural qualities, the massed figures cast as if cut from stone, powerful yet immobile. No doubt these features and their corresponding sense of “timelessness” made for such strong extension into posters, war bond drives, and, of course, a memorial statue. And one can see how this was achieved visually. In typical reproductions of the original photograph the scene is cropped vertically, as if a portrait, and shot slightly from below; the effect is to magnify the flag raisers against the scene which they dominate. Contrast this with the more recent photograph, cropped horizontally, as if in a landscape, and shot on a more or less level plane; the corresponding effect is to minimize the flag raiser who is now dwarfed by a scene dominated by the sky and the flag pole.

The scene, of course, sets the stage for action, and here, once again, the caption is telling, as it describes the lone flag raiser as fighting against the wind. It is not insignificant in this regard that in the Iwo Jima photograph the wind is to the back of the flag raisers, thus evoking the sense in which nature—and perhaps, by extension, providence—is on their side. Here nature is the enemy, and again, perhaps, with all that that entails. But more to the point, there doesn’t seem to be anything particularly heroic about replacing a flag pole knocked down by a sandstorm. If anything, the effort here seems more futile than monumental. Indeed, it is hard to shake the thought that this flag pole isn’t destined to be knocked down by many more sandstorms in the future. It is certainly hard to imagine anyone ever using this photograph as the template for a statue to memorialize the war.

It would be easy to conclude that the image above is the cynic’s answer to the war in Afghanistan, the longest war in U.S. history by a factor of two and going strong. And we should not be too quick to exclude that possibility or its implications. But at the same time we should be careful to take account of how our representations and remembrances of the “good war”—a war that ended in atrocity with the dropping of two nuclear bombs—goads the ways in which we think about our place in the world and thus inclines us to impose our own, idealized egalitarianism, nationalism, and civic virtue on other peoples.

Photo Credit: Denis Sinyako/Reuters

The “Advance of Civilization”

I had the opportunity this past week to visit the Museum of Westward Expansion which is part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and is housed underground beneath the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. According to the museum’s website it “preserves some of the rarest artifacts from the days of Lewis and Clark” and allows visitors to “explore the world of American Indians and the 19th-century pioneers who helped shape the history of the American West.” Imagine my surprise then when I came across the floor to ceiling photograph shown below in the middle of the first exhibit room dedicated to a timeline of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

You will of course recognize it as the iconic image of the “mushroom cloud” explosion over Nagasaki, the second of two atomic bombs dropped on Japan in August, 1945. Since this event has no obvious connection to the Louis and Clark Expedition, I expressed my surprise to one of the museum’s docents who responded by noting, “… the museum is [also] about the advance of civilization as part of the nation’s movement westward and we want to show some of the key moments from the twentieth century.” And indeed, not far from this display one finds a comparable floor to ceiling photograph of Neil Armstrong saluting the U.S. flag on the moon.

In as much as the space program was originally framed as an extension of the American frontier—marked here by the stage coach—the photograph of the moon landing makes a modicum of sense, but the explosion of a bomb that obliterated a city killing nearly forty thousand people and set off what became known as the Cold War’s “arms race” does not sit easily with the theme of the “advance of civilization,” and its connection to the notion of “westward expansion” is even more difficult to fathom.

Upon more careful inspection, however, I noticed that the photograph of the mushroom cloud, which otherwise lacked any caption or explanation, is inscribed with a quotation from Alfred Einstein in 1939 that reads: “… in the course of the last four months it has been made probable … that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium elements would be generated … This new phenomenon … would lead to the production of bombs and it is conceivable, though much less certain, that extremely powerful bombs of a new type constructed.” The quotation stands in odd opposition to the photograph itself inasmuch as it frames the bomb as a less than certain outcome of a scientific advance in nuclear technology. The bomb may have been “much less certain,” but sure enough here it is as a documented, photographic reality.

One might want to read this as a ham handed expression of America’s “manifest destiny,” and I don’t want to ignore the implications of that possibility. But I think there is another and more subtle point to be made. Einstein’s words precede the explosion by six years. And as such they caption the image in terms of what Hariman and I have described elsewhere as “modernity’s gamble,” the wager that the long-term dangers (and anxieties) of a technology-intensive society will be avoided (or managed) by continued progress. Yes, the ability to “set up a nuclear chain reaction” is a mark of scientific and technological progress, but of course it comes with a risk—the possibility of the production of “extremely powerful bombs of a new type.” That in this case the possibility became a catastrophic reality is mitigated by the necessities of the gamble itself, i.e., such risk is the cost of progress in an advanced technological society. And as the second photograph purports to show, sometimes the gamble pays off. The problem, of course, is that those who paid the costs of such gambles with their lives are nowhere to be seen in either photograph.

In short, the exhibit articulates our history of westward expansion with our cultural vow to technological progress, and as such it reinforces our commitment to the rationale of modernity’s gamble. More specifically, it contributes to the domestication of our memory and understanding of the explosion of the bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki by casting them as simple “advances in civilization.” And that should give us pause.

Photo Credit: John Louis Lucaites

Memorial Day in A Global Environment

1.3 millions Americans military personnel have lost their lives in wars since the founding of our nation. Memorial Day, invented after the Civil War, the most costly war in U.S. history accounting for nearly half of all such deaths, is a day for remembering their sacrifice. It should be a solemn day and one can only wonder why it has become as much a day for pre-summer sales and commerce as for remembrance. But there is another point to be made, which is simply tthat such remembrances and mourning is not just American but cosmopolitan. Somewhere between 22 and 25 million military personnel died in World War II (and that pales in comparison to the total loss of 62 million people overall). Of that 22-25 million, approximately 416,000 were Americans, a grim reminder that such remembrance and mourning should be located, at least in part, as a matter of cosmopolitan interest and concern.

The photograph above shows a slice of such remembrance, as the caption identifies a woman who pauses in the Potocari Cemetery (Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina), which holds the remains of some of the more than 8,000 victims of the Srebrenica massacre of July 1995, the largest mass murder in Europe since WWII. Bosnian Serb troops led by Ratko Mladic carried out a genocidal spree of rape and murder on the mostly Muslim refugees who were there, a previous UN ”safe area.”

Photo Credit: Fabrizio Lasorsa/Eidon Press/ZUMAPRESS.com

Visual Traces of a Democratic Public Culture

The above photograph is nearly fifty years old and I doubt that very many people recognize it—or for that matter have ever seen it before it was recently included in a slide show at The Big Picture—or can identify the event that it depicts and marks. I couldn’t. But it is nevertheless interesting for several reasons. For one thing it is a reminder of how homogenous the press corp was as recently as the mid-1960s. The site for this image is the Treaty Room in the White House and so it is possible that Helen Thomas can be found somewhere in the vicinity, but she certainly isn’t in this photograph which is not only lily white, but masculine to the core. For another thing, notice the flood lights that are illuminating the table and document being photographed, a reminder that image events and photo-ops have long been part of the political process. But what is perhaps most interesting is that apart from the journalists, there are no obvious political agents of action here. If we can assume that event marks the signing of a treaty, there is no direct evidence of who might have engineered or negotiated it and no evidence of who might take credit for it. The painting of presidents looking down upon the scene would seem to suggest that whatever victory is to be claimed here inheres in the presidency as a democratic institution and not an individual president. It is hard to imagine such a photograph being taken today.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, the photographers are huddled around the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which was signed by then President Kennedy on October 7, 1963. It was an incredibly important historical event given that concerns about above ground nuclear testing had been on the international public agenda since the middle of the Eisenhower administration in 1955. But no less important are contemporary efforts to manage nuclear arms through the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), a treaty that as recently as September 16, 2010 was endorsed by four republican members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, as well as a number of Republican stalwarts of national security, including Henry Kissinger, James Baker, and George Schultz. Even Patrick Buchanan notes that the Presidents he worked for—Nixon and Reagan—would have supported it. As of this morning, however, it appears that only one Republican Senator—Richard Lugar of Indiana—supports the treaty, while congressional Republican leadership in general seems determined to deny any and all initiatives by the Obama administration, notwithstanding any value they might have for something like national security or the possibility of movement towards a nuclear free world. Of course it is possible that Republican senators such as Christopher Bond of Missouri have good reasons to be skeptical of the verification standards built into the New Start treaty, and one can only hope that he will reveal the “secret” information he claims to have that supports his worries. Or perhaps John Kyl of Arizona is correct to try to “negotiate” for additional support to the $84 billion dollars already dedicated to “nuclear modernization” in return for his support, though its not clear how much would be enough to meet his concerns.

What does seem clear is that once a treaty is signed—and it is virtually inevitable that some treaty will be signed–whether in the lame duck session of Congress or once Republicans take control of the House in the new year we are unlikely to see a photograph like the one above where the Treaty itself is perhaps more important than those who brought it into being. And for future generations looking back on the politics of this time that too will offer interesting evidence of the state of our so-called democratic public culture

Photo Credit: Robert Knudsen, White House/John F. Kennedy Library

A Sporting Memory of 9/11

By guest corespondent Michael Butterworth:

At first glance, this photograph may appear well-suited to NCN’s category “boots and hands.” But the cleats of Chicago Cubs outfielder Alfonso Soriano are not the real story here, or at least not primarily so. While the foot commands our attention, the real focus is on how it directs the viewer’s gaze to the legend printed on the base: “We Shall Not Forget.”

Even the most casual observer of sports has likely noticed how commonplace such memorials have become. The sentiment should be simple enough: 9/11 was an event of such magnitude and consequence that it is incumbent upon us to remember the things which bind us together as a nation. And since such “binding” seems to be one of the socio-cultural functions of national sporting events, it is little surprise that they have become the perfect vehicle for circulating such memories.

While such declarations make it clear that we should not forget, what is left unstated is exactly what we are to remember. Note, for example, that we are not being asked to remember the actual events of 9/11 itself. Indeed, memorials like those found in this photograph are only partially about the past; as memorializing is more often a reflection of a community’s needs in the present. And the present here, of course, is defined by the so-called “war on terror,” a military campaign that is now only minimally about 9/11 itself. With this in mind, we can view “We Shall Not Forget” as it overlaps with the numerous visions of militarism that have become woven into the fabric of sports—from red, white, and blue emblazoned ball caps, to military flyovers, to museum exhibitions—and conclude that sports in the United States continue to contribute to the normalization of a problematic war.

The tragedy in this is that the photograph reminds us that it needn’t have turned out this way. Behind Soriano’s carefully balanced cleats is the blurry image of the Miller Park outfield grass. Baseball mythology is grounded in, among other things, the idea that the ballpark represents a pastoral sanctuary—a metaphor of the countryside that offers comfort, security, and community. Although that mythology can be flawed, 9/11 precipitated a rare moment when the “national pastime” really did invite all Americans to participate in an imagined community, one based on genuine human needs laid bare in the wake of the terrorist attacks.

All too quickly, those initial ceremonies—of mourning, of healing, of hope—that took place in baseball stadiums in September and October of 2001, gave way to belligerent expressions of hot patriotism and militaristic vengeance. This photograph reminds us that in the days, months, and years after 9/11 there was a more humane and less violent path available to us. Now, just like the outfield grass in this photo, that path seems blurry and somehow out of reach. How easily we have forgotten, after all.

Photo Credit: Jeffrey Phelps/AP Photo

Michael Butterworth is an assistant professor of communication in the School of Media and Communication at Bowling Green State University and host of The Agon, a blog on rhetoric, sport, and political culture. Michael is also the author of the recently published Baseball and Rhetorics of Purity: The National Pastime and American Identity During the War on Terror (University of Alabama Press, 2010). He can be contacted at mbutter@bgsu.edu.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

(Re)membering 9/11 in the Future

I am currently teaching a senior seminar on photojournalism and civic culture and it should come as no surprise that we have spent some time this past week discussing the ways in which photography contributes to how we remember and memorialize the most recent day of infamy in U.S. history. After a recent class one of my students wrote with a question, wondering why it was that there are so many pictures of firefighters at ground zero and no pictures of “the Pennsylvania flight or the DC attack.” Of course, such pictures do exist and they have had some distribution and circulation, but nevertheless the sense of the question is dead on correct: for the most part we have remembered the 9/11 attacks photographically in terms of New York City and the heroic efforts of hundreds of firefighters. The photograph above, which led off a recent slide show on 9/11 remembrance at The Big Picture offers some hints as to why.

The focal point of the photograph is the pink rose being offered by a young boy to a firefighter. The child appears to be happy, safe and secure on his fathers shoulders; but more, his pose—cast against a cloudless, bright blue sky—suggests a return of the innocence that had been purportedly erased once and for all on that fateful day, nine years ago. The dark pink rose, of course, is a symbol of gratitude and appreciation, and its significance here is enhanced by the fact that it is being offered backwards from a representative of a future generation to a representative of the earlier generation whose sacrifices made the present possible. But that is not exactly right, as the offer of gratitude is not simply from one generation to another, but from a citizen to a representative of the state. That the citizen is cast as a pre-adolescent child is very much to the point as it prefigures the parental role of the state. And therein perhaps lies one of the reasons why the firefighter has become such an iconic representation of 9/11, as well as why we see so few pictures of the assault on the Pentagon. Although no one is to blame, images of a successful sneak attack against the nation’s premiere citadel hardly inspires confidence in the ability of the state to protect its citizenry; by the same token, the New York City firefighters more than rose to the task in responding to an attack against a public site.

But there is more going on in this photograph than an allegory of parens patria. And to see what you need to look more closely at the deep background, shot in soft focus, that blends the vivid blue sky with erection of the new tower. That the emergent tower is aligned with the child, and thus identified with a bright future is not incidental, but the bigger point is that the landscape background serves to frame the events on the ground. The effect of that framing is to redirect our remembrances of 9/11 away from a narrative of trauma and loss and towards an unreflexive and over weaning pride—one might even say hubris— in our ability to rebuild and reconstruct, a point underscored throughout the slide show (e.g., here, here, here, and here), but emphasized elsewhere as well, as with photographs such as this one of a father and son appearing to admire the construction site for the new World Trade Center.

The full implications of conflating remembrance (of the past) with rebuilding (the future) are a bit unclear, but they are also somewhat unsettling. Emphasizing the trope of “rebuilding” no doubt draws attention to Ground Zero more than to other sites of 9/11 memory, and in that sense it might help to explain why we see so relatively few photographs from Pennsylvania or Washington D.C, where there are no easily recognizable rebuilding projects. But it should also lead us to notice a potential shift in attention away from the firefighter as hero to the construction worker, and by extension from the state to the private sector. That shift is underscored by the fact that the new tower, originally identified as “Freedom Tower,” has more recently been dubbed “One World Trade Center,” almost as if to shed its connection with the world of state politics and to locate it back in the world of capital and commerce. And what better site for that than New York City? And so it is that the two photographs above seem to work in close tandem with one another: in the first the child must turn around awkwardly to address the firefighter who, it turns out, is barely in the frame, seemingly fading into the past and perhaps soon to be forgotten altogether, or remembered as little more than a relic of a distant time and place; in the second image, father and son comfortably cast the gaze of multiple generations ahead to the future.

It made me recall the words of George Santayana. Not just his prophecy that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but also that “Those who speak most of progress measure it by quantity and not quality.”

Photo Credit: CHang Lee/AP Photo; Spencer Platt/Getty Images.