By guest correspondent Patrick Wade.

As long as we are cataloging historical moments of American injustice, violence, protest, and trauma in early May–and their importance for ongoing memory-work “in the interest of a usable past”–we shouldn’t forget about the labor dimension of May Day, and its origins in the Haymarket tragedy of May 4, 1886.

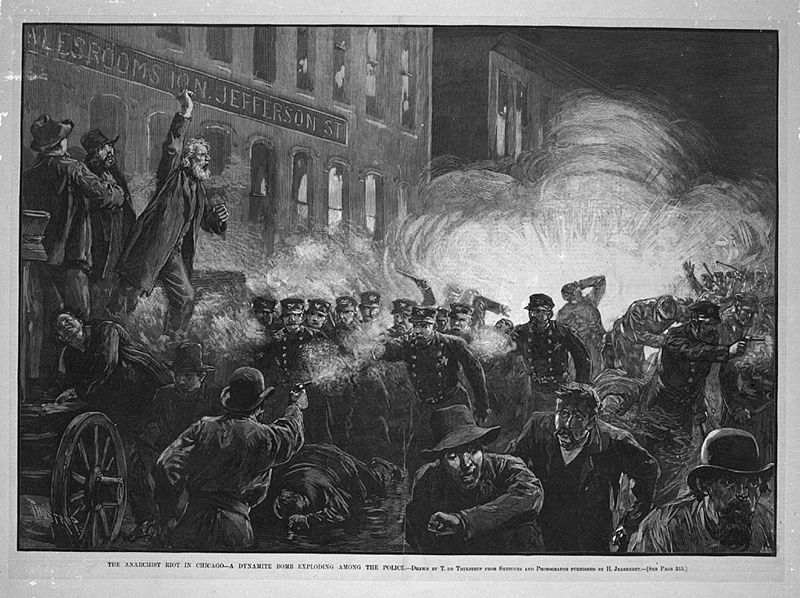

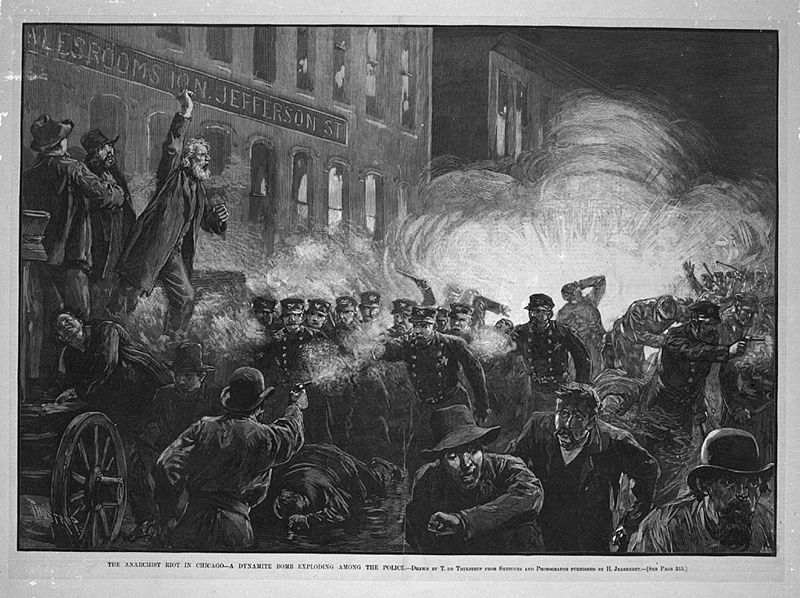

On May 3, Chicago police officers killed two strikers in a fight at McCormick Reaper Works. In response to the killing, a meeting was called by August Spies and Albert Parsons at Chicago’s Haymarket square. As the meeting was winding down and Samuel Fielden, the evening’s final orator, was speaking, 175 Chicago police officers marched on the gathering and demanded that the remaining crowd disperse. An unidentified person in the crowd threw a dynamite bomb into the police ranks, instantly slaying Officer Matthias Deegan and wounding several others. The police began to fire into the crowd, and, in the aftermath, eight prominent anarchists and labor leaders were arrested and tried for murder. Five were executed by hanging, although Chicago Mayor John Peter Altgeld would later pardon the survivors and exonerate the executed, as none of the men could be proven to have taken part in any conspiracy to murder.

On May 15th, 11 days following the initial events, Harper’s magazine published the illustration that you see above. The image–like much of the editorial commentary at the time–blamed anarchists and labor agitators for violence. Samuel Fielden is pictured exhorting the crowd in spite of the melee unfolding below him. One crowd member is shown firing on the police. The image depicts a riot, one with villains (the crowd) and heroes (the police). The illustration is composing a useable past–for the state.

Photography’s realism doesn’t hinder depictions of “wild” crowds of protesters to paint dissent as illegitimate, blameworthy acts of violence against the legitimate guarantors of social order. We would do well to remember this as we look at contemporary news stories displaying the violent outcomes of May Day rallies across Europe. See, for example, the MSNBC.com article “May Day Turns Violent across Europe, or the New York Times article “Anger and Fear Fuel May Day Protests.”

Conventional images of protest such as this foreground the wild-eyed, long-haired, bearded anarchist as a threat to the social order. And are images like the one below, that represent the “pure” possibilities of peaceful protest, any less naive in their erasure of the inherent potential for violence in the gathering of crowds?

When the New York Times leads the online version of its story about European May Day protest with this image, the viewer is encouraged to see legitimate protest as serenely peaceful, which makes images of violent protest distressful, disturbing, and illegitimate by comparison.

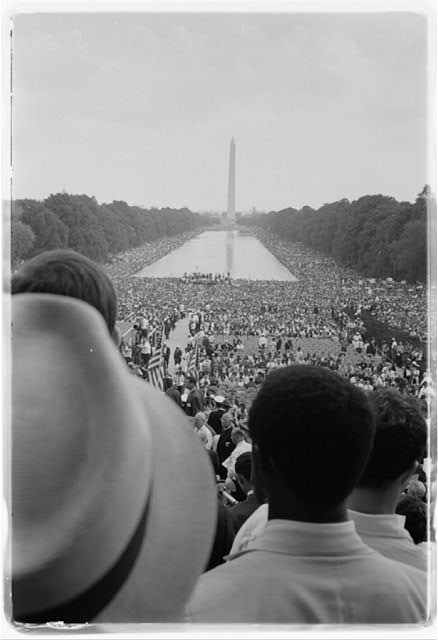

But of course, we need not be trapped between these two images of protest. There is a third, democratic possibility, one that relies on a different strategy that falls outside of the play of guilt and innocence in the two photographs above.

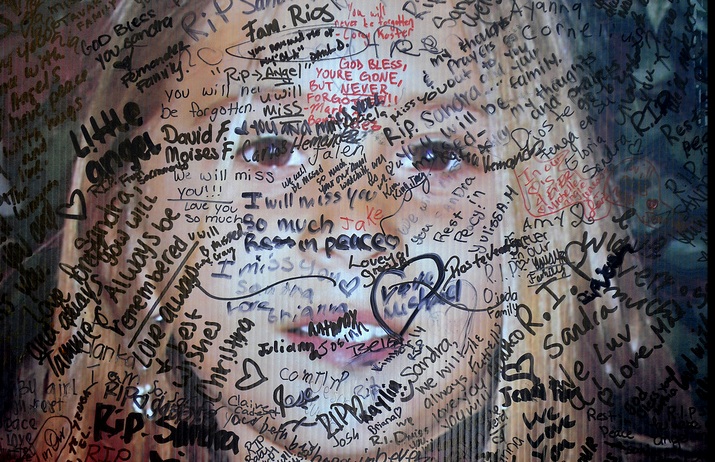

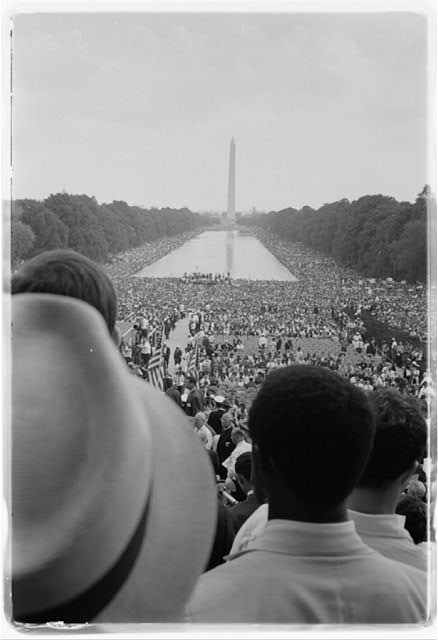

Here we see a photograph of the community gathering together to engage in collective action to bring about change. The crowd is always potentially violent, and this is part of its strength. But this violence is always implicit, and it creates the possibility of a political demand–one that can best be represented in the gathering of bodies together in a collective, embodied argument, under a banner, in plain view of a seat of governmental power.

Can we not draw a further parallel to a different photograph, another image of a crowd taken from the civil rights movement in the US? One that draws upon all the aesthetic powers of photographic design to eloquently depict collective solidarity?

Yes we can.

Illustration by Harper/s Weekly/public domain. Photographs by Mustafa Ozer/Agence France Press – Getty Images; Fred Dufour/Agence France Press – Getty Images; Lucas Dolega/European Pressphoto Agency; Warren Leffler/US News and World Report. Patrick Wade is a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University. He can be contacted at wpatrickwade at gmail.com.

0 Comments