The third Monday of April is celebrated as Patriot’s Day in commemoration of the battle of Lexington and Concord. Since 1998 it has coincided with In Memory Day, a memorial remembrance held at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial for those who “died as a result of the Vietnam War, but whose deaths do not fit DOD criteria for inclusion upon the wall.” It is hard to know just how many of the 3.5 million men and women who served in Vietnam fit in this category, but the In Memory Day Honor Roll now includes 1,800 names, most of them having died as a result of the effects of “Agent Orange exposure or emotional wounds that never healed.”

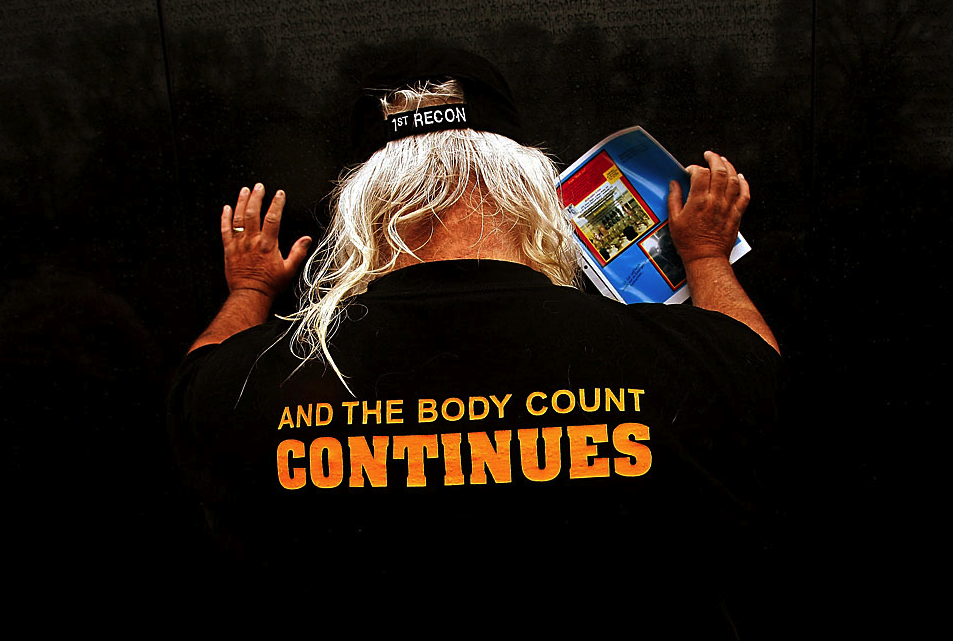

There are numerous photographs of the event but the one above of an anonymous veteran putting his hands on the Wall is perhaps the most visually provocative. Shot from behind and in medium close distance, the polished black surface of the granite blends almost perfectly with the black t-shirt and hat, inviting the momentary illusion that the veteran is literally one with the Wall. Only the glare and shadows near the very top of the image disrupt the spell by just barely illuminating the names etched into the Memorial and thus invoking the linear perspective that enables a degree of visual separation between the two; at the same time, however, that very perspective complicates our understanding of the relationship between those who died in combat and those who presumably survived the conflict only to contribute to the “body count” in a different register. That tension is further underscored visually by the way in which the orangish tint of his arms and hands draw our attention from the black Wall to the orange legend on the back of his t-shirt, a stark verbal reminder that the devastating human costs of the Vietnam War have extended—and continue to extend—long past the final battle and retreat. The red, white, and blue matting that frames the photo he holds up to the wall is an equally poignant reminder of where the responsibility lies—not with individual soldiers, anonymous or etched in stone, but with the nation state that fostered the war in the first place.

If the photograph was simply a journalistic representation of a particular memorial event, or more, even an evocative representation of the continuing sufferance of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, it would easily deserve to be displayed throughout the land for citizens and leaders alike to see and contemplate. But the context for interpreting the meaning of the image cannot be so easily contained, especially at our current moment in history as the war in Iraq morphs into the war in Afghanistan, and so the photograph speaks in more than a simple or literal voice.

By official estimates there have been 4,274 U.S. military deaths in Iraq since the beginning of the war in 2003 plus an additional 678 U.S. military deaths in Afghanistan. But if our Vietnam experience has taught us anything it is that such literal “body counts” are only the beginning. By even the most conservative estimates 1 in 6 (or 16%) of all returning veterans from Iraq suffer from some form of PTSD (i.e., “emotional wounds that never heal”) that has been linked to excessive levels of obesity, alcoholism, and drug addiction, as well as “epidemic” levels of suicide—with far too few getting needed or effective treatment. As in the past, it is often difficult to see such psychic wounds, or worse, it is all too easy to see past them; and yet, as the photograph above seems to suggest, the degrees of separation between combat deaths and other forms of the “body count” is often something of an illusion that we retain at our own peril.

And so the photograph takes on the quality of an allegory for the complexity of war’s costs; indeed, perhaps it is a visual analog to George Santayana’s warning that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Photo Credit: Win McNamee/Getty IMages