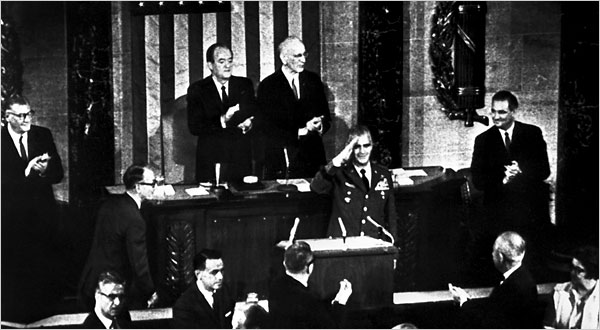

The NYT published this diptych in a story titled “Race and Gender are Issues in Tense Day for Democrats.” The story is a “he-said, she said” tale that is implicitly about who gets to play the race card in the on-going democratic primaries. Apparently Barack Obama should be able to, but doesn’t want to (because presumably he doesn’t have to in order to preserve his base); Hillary Clinton apparently does play it, but in an allegedly backhanded way that allows her to underscore her own marginalized status as a woman (thus, presumably to energize her base). The issue comes down to a debate about the relationship between race and gender, as if, at the end of the day, we should decide our votes somehow on who is more marginalized than the other. The photograph that accompanies the story – and is nowhere remarked upon, and thus might appear to be something of an excess – tells a somewhat different tale.

The key here is in understanding how the stark tension between race and gender is muted by attention to more complex generational differences. To see how, envision one set of hands as white and female, the other as black and male. How would each be inclined to vote? The lines of identification would seem to be pretty obvious, driven by both race and gender in each direction. And indeed, it is this stark and uncomplicated dialectic that the NYT exploited on Sunday when it juxtaposed images of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Frederick Douglass in a story that featured what Michael Shaw at BAGnewsNotes called the “pink-black divide.” But notice that the demographic put on display in the above diptych is much more complex, as the images feature the much harder case: How do African-American women who share identities with both candidates choose? Will they be guided by their racial identity or their gender?

And the answer we get is a study in ambiguity that takes the false essentialism of identity politics to task—or at least it complicates it in ways that bear consideration. Thus, while both sets of hands are clearly female and African-American, there are nevertheless important and notable differences that mark something of a subtle, but complex and significant generational divide. To begin, take note of the fact that these are neither young nor inexperienced hands. Each pair is clearly weathered by the passage of time and the accumulation of experience, but they wear their experiences differently. The hands on the left bear a feminine style that associates them with the feminist politics of the 1970s, where the cosmetics that we traditionally affiliate with female sexuality were somewhat muted. Notice how the fingernails are carefully trimmed and without polish. They are adorned by rings that mark them as female, to be sure, but they are folded in a somewhat pragmatic, masculine fashion that underscores the attitudes about gender equality that animated many women in the post-civil rights generation of the 1970s. Indeed, they seem to be protecting the poster, a symbol of the political world and the public sphere that was opened to women by the efforts of second wave feminism.

The hands on the right present a somewhat different, older, feminine style, with more rings, and long, painted fingernails. The pose is more traditionally feminine as well, as the hands rest in the woman’s lap, gently holding a snapshot. And unlike the poster, the snapshot signifies the private, domestic sphere – the world of family photo albums – to which women have traditionally been relegated in a patriarchal order. In a world of cultural stereotypes then, these are the hands of a woman who, in all likelihood, comes from an earlier generation than the woman on the left. She is perhaps old enough to have participated in a sit-in in Mississippi or to have marched in Washington, D.C. From this perspective, the snapshot she holds may well be the cipher for an emotional aide de memoire to her youth, as the picture of Obama recalls the eloquence and charisma of John F. Kennedy or Martin Luther King, Jr., young, men whose uplifting appeals to a color blind society no doubt resonate with her candidates’ eloquent promises for a changed world. Indeed, his very candidacy may serve as the evidence that the struggles of the civil rights generation were not for naught. In this register it is little wonder why some might have interpreted Clinton’s recent comments about Dr. King’s role in bringing about the Civil Rights Voting Act as derisive.

If experienced African-American women can be so divided over their support for Obama and Clinton, then it should be clear that there is something more complicated going on in this political campaign than a simple race-gender opposition. Here that complication is a somewhat subtle divide between maturing generations, but in other contexts it is no doubt something else. The diptych underscores the centrality of such impediments to the interpretive process, however, by forcing the viewer to negotiate such complexities and instabilities of meaning as a condition of even the simplest reading of the images. Note in this regard how the poster on the left is designed to be displayed in a horizontal plane, but here it is out of kilter, held on a slanted, vertical plane that is further obscured by the hands. The photograph on the right is even more askew. The effect is to force the viewer to have to strain to figure out what it is that they are seeing, tilting their head to the left to decipher the poster (and to guess at what the missing hidden letters might be) and then squinting to take account of the snapshot. One has no choice but to be an active reader/viewer.

The ultimate point I want to emphasize here is that the diptych calls to our attention a more important and complex tension in the current democratic primaries than the simple, faux battle between race and gender being crafted and preached by those who would prefer to see two historically marginalized groups doing battle with one another rather than working in solidarity. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t differences that have to be negotiated here, or that there isn’t a great deal at stake in the various generational divides (and there is clearly more than one) that seem to vex the democratic party at this historical juncture. But what it should also remind us is that we need to keep our eyes on the prize rather than to be distracted by reporters with time on their hands.

Photo Credits: Todd Heisler/New York Times; Eric Thayer/New York Times