The war in Iraq and Afghanistan is slowly edging back into US public media, but it’s still easy to miss. The problem isn’t only that so much attention is being given to the debates about health care (or the lack of it) and financial regulation (or that lack of it) and the continuing problems in each sector (see “lack,” above). The war coverage itself has a peculiar cast: instead of deployments, patrols, firefights, and other action shots, there have been a stream of images that show wreckage, rubble, and similar scenes of destruction. Scenes like this:

A man walks slowly along Cairo Street in Baghdad in the aftermath of a bombing. The bomb obviously was huge, leaving a vast swath of mangled metal and broken lives. What you don’t see is a field of battle; instead, this is a civilian street, complete with a cobblestone median and an institutional building in the background. The picture might be said to lend plausible deniability to the idea that there still is a real war going on in Iraq. The lone figure in the foreground suggests as much. He is every inch a civilian, and his pensive posture suggests that this is a time for reflection, not action.

The flag is still flying, and officials and soldiers far in the rear will oversee the clean-up, but the large space between them and the lone individual in the front is empty of people, as if the society itself had been vaporized in the blast. The war is there but not there, while the social, ethnic, religious, and political motivations for the bombings are unintelligible. A bomb detonates, and a man muses. Apparently, there is nothing for him–or anyone else–to do but to walk on into the unknown future that lies outside the frame. Like this:

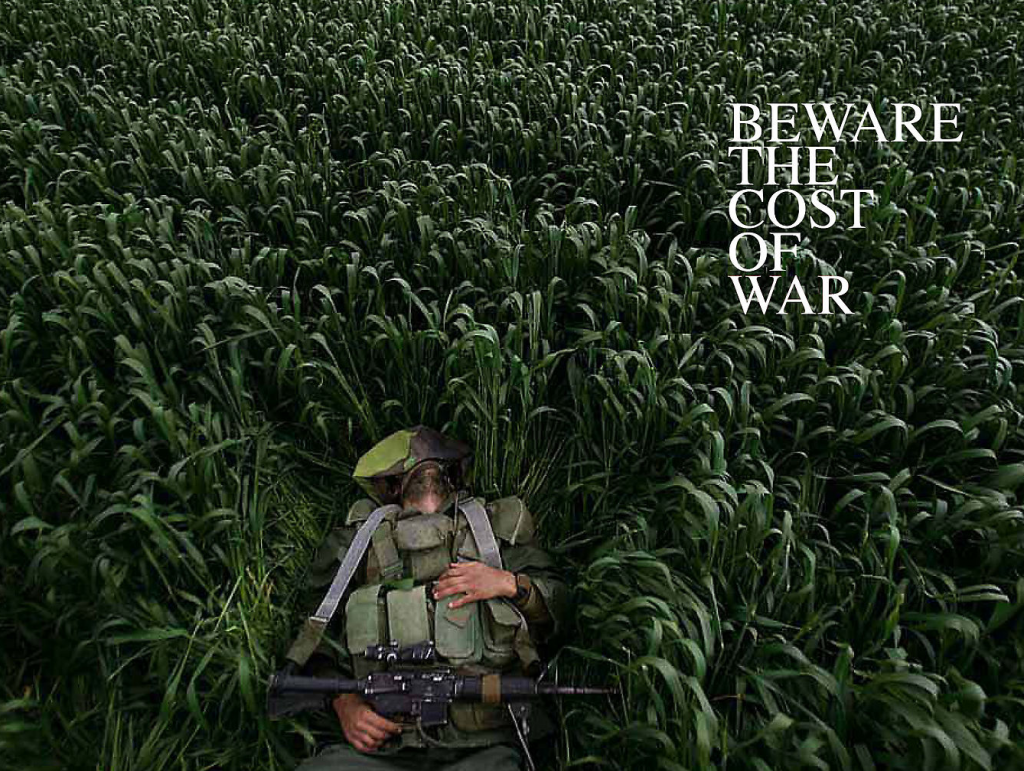

There have been dozens of photographs similar to this one in the past several weeks: photos of US troops standing around or slowly walking through places that are otherwise empty. Often enough, they are scenes of destruction, but the act is already in the past, something that occurred off camera. The troops aren’t fighting so much as overseeing an impersonal process of destruction. And that process seems to involve razing city streets and vehicles more than anything else; again, the people that would normally fill the scene have been ghosted away.

Note the many other similarities with the first photo. Again, officials hold down the rear of the scene, while a single person walks toward the space to the right of the frame. His mood is not identical to the man above, but he does seem both turned inward and weighed down, and, again, there is nothing to be done about what has happened. He is merely going through the motions to “secure the area”: an area already secured by the scythe of the bomb’s blast.

Such photos may reflect that fact that US policy has been in a state of limbo for the past few months, but they also may suggest that the US war effort has become something like a permanent state between war and peace, an intermediate place of suspension and neglect. Worse, they may suggest that this is acceptable because the US troops are just passing through. They are there for awhile but not really doing much, and eventually they’ll rotate out and leave the place to its fate as one of the boroughs of rubble world.

And so there is reason to look at the first photograph again, for there may be an important difference between the two after all. Despite his ability to do much more than walk through the scene, there is little doubt that he lives there. If that isn’t his street, it’s his city; if not his city, it’s continuous with where he does live. He thinks, smokes, and walks on, but his future will be in that place. And to see him there is to see someone who belongs in the photograph, whose presence speaks to something valuable there, and who provides a point of contact for the viewer. To the extent that we can see him as being in the picture, we are pulled into the frame as well, and asked to witness and reflect on what is there and why.

By contrast, it seems very clear that the soldier is just passing through. Whatever his presence may provoke, the message is that he really isn’t a part of the scene. If we walk with him, it’s to appreciate his wish to get through it alive, but not to stay in, understand, and commit to that place.

Each photograph–any photograph–presents the viewer with a choice about how much one might be in the picture. In both of these two photos, the choice to the US viewer is skewed toward minimal involvement: one figure is a foreign national in his homeland, and the other is a US soldier far from home. Even so, the first image may also evoke a compassionate response. With the second image, however, it’s just a matter of time before we can pretend that there is no one there.

Photographs by Ahmad Al-Rubaye/AFP-Getty Images and Reuters (Wall Street Journal).

0 Comments