One of the important features of public culture today is that globalization has become a social fact. For example, economic historians can document that the world has had a global economy for centuries, but now people know that they live in a global economy, and many people know this, and they know it not only in New York and London but also in Peoria and Bangladesh. At the same time, it would be a mistake to conclude that this shared social knowledge carries with it a common map of the world. To the contrary, another interesting facet of the 21st century is the emergence of multiple geographies. One still acquires a geography of nation states, but amidst that there are diasporic communities, media capitols, free trade zones, black markets, clashing civilizations, greater Kurdistan, the New Caliphate, and perhaps someday the fabled Northwest Passage.

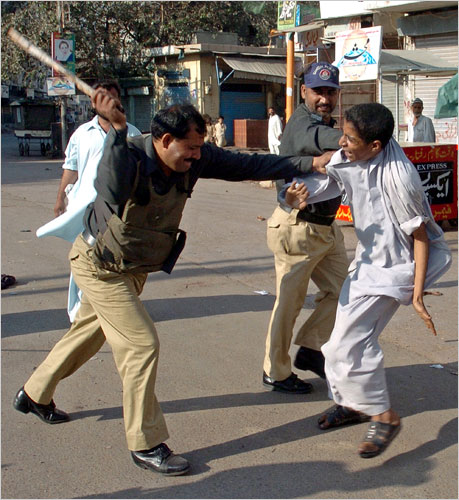

This melange of borders, flows, and visions is not yet a social fact, but it is not merely academic speculation either. One sign that the maps are changing is that the terms First World/Second World/Third World are becoming increasingly outdated, although not because hierarchies are being leveled. Let me suggest that something else is being leveled, and offer one suggestion for a more up to date map. What matters today for a significant number of people is whether you live in Rubble World:

This photograph is from Baghdad. But it also could have been in Beirut, like this one:

Or, most recently, Gaza:

These are without a doubt among the leaders in the field, but let’s not forget Grozny and Sarejevo, among others. And then there are the periodic terrorist bombings in Kashmir, New Delhi, Sri Lanki, or wherever, not to mention Ground Zero in New York. Nor should we limit ourselves to the devastation of war, as the combination of poverty and political failure allows quakes, typhoons, and plain old shoddy construction due to corruption to add to the pile. Type “rubble” into Google Image and you can begin your guided tour of Rubble World.

If you take that tour you might notice that many of the images look very similar to the three here. Rubble World doesn’t start from scratch: there has to be something to wreck first. Like war itself, it is parasitic. The curious thing is that it seems as if everything still is pretty much as before–say, as if only the facade of the building has been blown off, or the wallboards and mattresses rearranged. The blast exposes building infrastructure or leaves people gathered together on the ground as if they were in a house, but you might think that everything important remains in place. That is a lie, of course. The buildings have to be condemned, and rebuilding can’t even begin until the all the work and expense of clearing the site has been completed. We are looking at skeletons, not at disruption; not a setback but ruin.

And so we get to the people–those still alive, that is. Rubble World is not uninhabited. As in many of its images, the people here are reduced to being spectators to their own desolation. There are many such scenes, whether of a few people in the urban ravine or of a small gathering of neighbors trying out their new status as squatters on their own property. Each might be a sign of hope. The urban space can be rebuilt only if citizens survey the damage and begin to talk about how to to organize. The local community can only survive if people remain attentive to one another amidst danger. Even so, these people have all been idled. The loss is not limited to an apartment building or a house, but spreads like a blast pattern across the entire economy. Rubble World includes some stories of renewal, but the total losses of productivity, prosperity, and hope itself are staggering. By documenting architectural wreakage, these images reveal how civil society is being laid bare, torn apart, damaged, and dispersed. As that happens, the rubble is sure to spread.

Photographs by Associated Press; Getty Images; Abid Katib/Getty Images.