I guess the war in Iraq turned out OK after all. That’s the conclusion to be drawn from recent newspaper coverage. The photos are devoted to showing Iraqis relaxing in the park or shopping, or US soldiers who don’t seem to do anything except dispense medical care or play with kids. The verbal reports are much the same. Oh, some bad news is there. On Saturday 11 people were killed in several incidents, but you had to read page 21 of the New York Times to know it. While US deaths are at 3893, the tally for November was only about one per day; down from four a day in May and two a day in September, just a trickle really.

So it is that we are on the verge of another betrayal: it is becoming all too easy for the American public to pretend that the war is winding down successfully and that the losses really weren’t so bad. I’d suggest we take another look at the war. This, for example:

This is from a story in the December 2006 National Geographic. That magazine is no longer the epitome of middlebrow distraction that it once was. The photographs by James Nachtwey provide wrenching witness to the horrific price paid by so many soldiers who die or are horribly maimed despite the heroic efforts of the medical corps to save them.

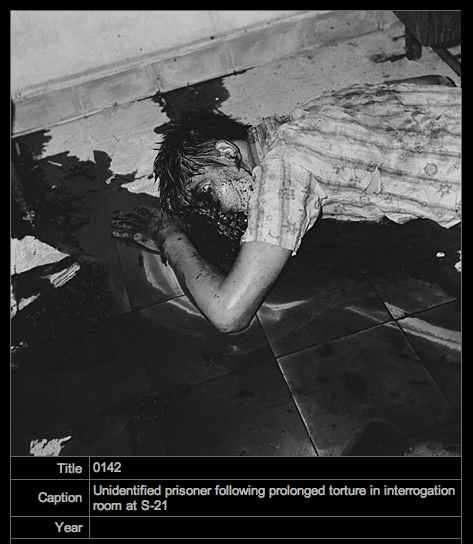

This photo of damage done by an IED blast is somehow intensely intimate. Perhaps because the boots look like Converse high tops, or the open wounds on the bare legs, or the fact that he doesn’t look too banged up, almost as if these were legs scraped badly in a game of sandlot baseball. You are instantly brought to care for the wounded boy and to be grateful that he will receive first rate care. He did receive first rate care, and he died anyway.

Just like this guy:

I saw this photograph a year ago, and it has been with me ever since.

In his odd, haunting novel about the Vietnam era, A Short Rhetoric for Leaving the Family, Peter Dimock’s narrator sets out to “invent some public speech with which to make the presence of the dead visible: some other history, some practical method by which to be able to speak capably concerning those things which law and custom have assigned to the uses of citizenship” (p. 29). It is the citizen’s duty to keep the dead present in memory, especially when they have died in a mistaken war. To do so requires some ability to resist official discourses and other forms of inattentiveness and amnesia. This can be done with speech and thus with the resources of classical rhetoric featured in the novel. Nachtwey demonstrates how it also can be done with photography.

The Right is crowing that the surge worked, while the Left is resigned to point out that it worked only because force levels were brought closer to what the Pentagon had requested and the Bush administration denied for the previous four years. And what is forgotten in this distorted debate? The simple fact that the surge can never restore what has already been irrevocably, senselessly lost.

There may be no harm in recognizing small victories, but good news should never be used to deny the presence of the dead. It is one thing to take credit where credit is due, and quite another to avoid responsibility for the past. And we do worse yet if we forget about those still to die.

Photographs by James Nachtwey for National Geographic. For the record, this month the total casualty figure for the occupation of Iraq exceeded 25,000 US troops, with an estimated Iraqi death toll at 1, 132, 766.