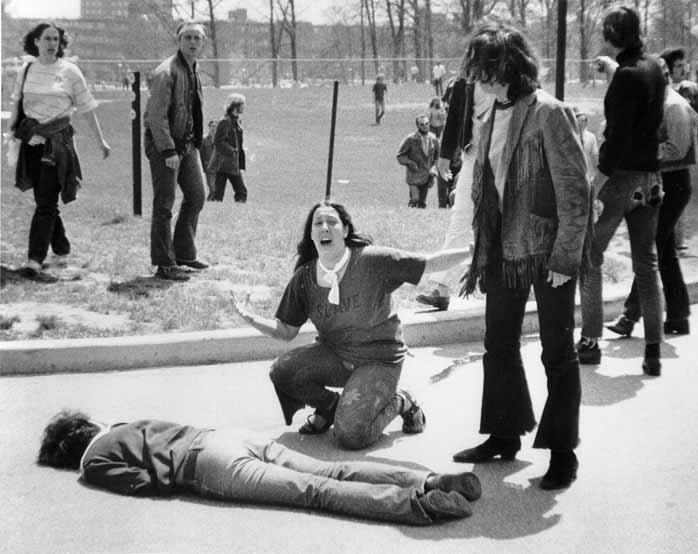

It is said that the eyes are the window of the soul. I hope not, and here’s why:

The boy is looking into a car not long after mercenaries in the employ of the U.S. government had destroyed the two women in the front seat. Every line of the Times story provides evidence of how this criminal war has gone all but completely out of control. I could write for hours about how much is revealed by the incident, where, once again, innocents are slaughtered for supposedly threatening “security” forces that shouldn’t be there in the first place. And then there is the unholy mix of agencies and companies involved: AID, a “quasi-independent agency” of the State Department, hired RTI International, which hired “Unity Resources Group, an Australian-run security firm that has its headquarters in Dubai and is registered in Singapore.” And let us not overlook the language used by the Times, which labeled the mercenaries “contractors” in the print edition and “guards” online, both euphemisms.

But all that I might say pales next to the mute testimony given by this photo. The photographer has used the most common elements of visual composition to focus our attention on something extraordinary. We see the boy’s face in the center of the picture; he is isolated against a soft-toned background as in studio portraiture; successively tighter framings by the border of the photo, the left side window, and the right side window channel our attention to his expression; his face is soft, his eyes are wide open. His acute vulnerability is accentuated by the contrast with the blurry smear of blood on the metal surface in the foreground. Between the left door and the boy lies the interior of the car, now a dark, gory killing pen. He has looked down and seen the stain inside. He looks up, as if for an answer.

The photograph shows us many things, but the achievement is to show seeing–real seeing, when you can’t necessarily filter out or fully comprehend what you see–and to show how we are affected by what comes in through our eyes. This child has seen the traces of horror within that car without benefit of geopolitical framing or any other adult defense mechanism. And he has been harmed.

As with the rest of the composition, nothing new is involved: we see people seeing as they look back at the camera in one snapshot after another. We enjoy reaction shots when the birthday gifts are opened. But that isn’t really seeing, for everyone knows how to react and no damage is likely to be done. And we’re not in a war zone.

This blog has posted several times on the normalization of war in the U.S. We also try to point out how photojournalists are documenting the reverse process, the destruction of the basic requirements for normal life for those trapped in Iraq. Children will always try to see what is happening. There are some things they just shouldn’t have to see.

Photograph by Joao Silva for The New York Times.