By guest correspondent Jeremy Gordon

Seeing dirt in combat zones is nothing new. In accounts of combat and its aftermath, terrain becomes a living entity, both working in terms of physical contact and mystical dimensions. The grounds are alive, swallowing bodies in rice fields, suffocating men in trenches, and blinding convoys in deserts. But they also offer places to cling to at the screams of a falling mortar round. It is a sordid relationship, cyclical in nature, turning to dirt for safety and death, sorrow and elation of near misses. There is a constant movement to and from the earth, going to it for safety and attempting to control its unruliness with concoctions and machinery, trying to keep tabs on it so it does note betray you.

Drawing lines in the sand with barbed wire is one such consistent method, as seen above. The earth shakers on the highway in the background rumble by on pavement paying little heed to the mounds and bushes to the side. Their pace is consistent as the space between the personnel carrier and the two other vehicles is fairly even, a measured and rational approach to traversing landscape. They blur into the horizon with a linear direction and time. The soldier nearest us wears no gloves, perhaps a sign of confidence and experience in the dirty work of war. Not rushing, he bends over at the right distance so as not to be cut. The gun is slacked on his back. The pace and direction of the action is somewhat contradictory to the convoy, as there is a sense of care in the arrangement of the wire, a ritual that serves to form barriers between bodies and space, safety, and danger. The wire then works as a frame, a barbed optic and cordoned view through which combat is expressed.

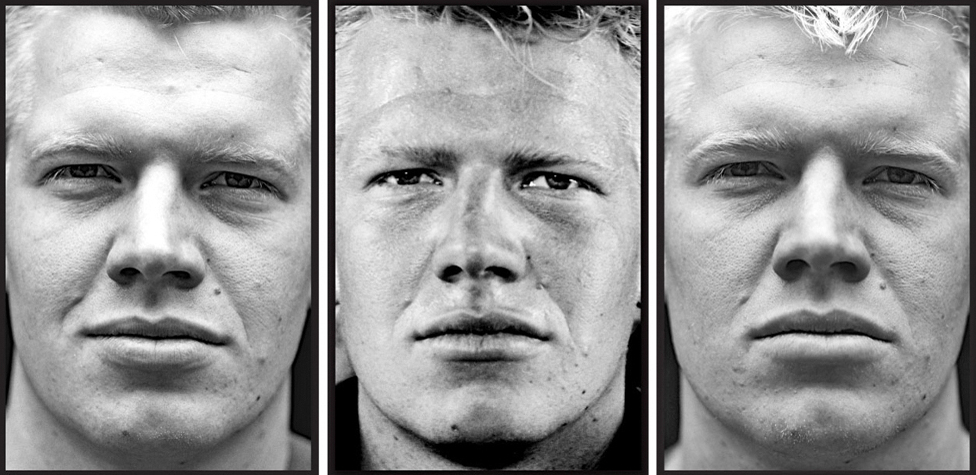

We might surmise that the optic changes post-deployment when treatments are scheduled and predictable, away from the dirt of the body, cleansed of pollution, pieces of trash stuck by barbs. The move is away from the dirty work of war. Maybe.

This image is part of a NYT slide show that accompanied a story about a veteran transition program training combat vets in organic farming. Literally framed in terms of “dirty work,” the article cites a “veteran-centric” farming movement. The “centric” thematic should not be ignored here, as now irrigation hoses, circular, yet tangled, frame our view of both men. Soldiers still work to roll out and arrange, the optic is similar, but the relationship to dirt is much different. The men maintain relaxed yet focused poses. The barbs are gone, but not the suspicion. One looks directly back through the circle, the other ponders, arms folded, looking off to the distance with an air doubt.

The rural setting, tree-lined fields and fertile soil, its pace, and farming’s inherent concerns with seasons of circularity rather than linear narratives of completeness provide an optic through which we might reconsider hyper-rational cleansing narratives of post-combat trauma. Here there is a circular patterns in which sorrow of death and joy of life are connected, where physical contact with dirt can be joined with mystical elements, linking bodily and soulful healing.

Such a cyclical approach to wholeness is not an escape from dirt but a shift in relation, from a season of wilting to a season of cultivation and rejuvenation. Seeing the combat narrative this way then is not a story of Homer’s Odysseus and the treacherous journey from Troy to an end of the Odyssey, but an echo of the Hymn to Demeter. Demeter was one of the earth gods in whose name a civic festival celebrating the cyclical nature of joy, sorrow, earth, agriculture, cultivation, and rejuvenation sought to change relationships to life and death, body and soul. The earth, like Demeter, knows mourning and elation, and as such, rituals that joined these were deeply rooted in the rural, agrarian Mysteries of Eleusis, secret rites in which initiates’ were changed through experience of “kinship between soul and bodies.” Rather than looking up, yearning to flee pollution and clean dirt from hands, changing our gaze only slightly reveals another optical style where unwinding wire brings us full circle, turning approaches to trauma to chances for labors of focused, relaxed, contingent, patient, and seasonal soiled work of rejuvenation.

Similus similibus curantur, loosely “relief by means of similars,” by means of unwinding coils of separation.

Photo Credits: Lushpix/StockPhotoPro; Sandy Huffaker/NYT

Jeremy Gordon is a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication and Culture, Indiana University. He can be contacted at jeregord@indiana.edu.

0 Comments