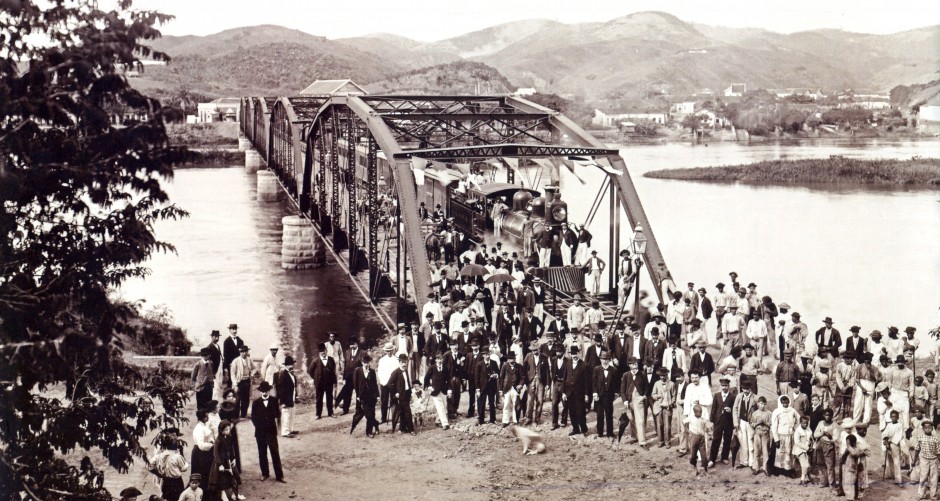

It’s not quite a Monet, but I think it deserves to framed. Cezanne might be the better comparison, but this photo is more about distance than mass and volume. And curiously, just where it gets close to abstraction, it also gets closest to the stiff demarcations and solid identities of American folk art, which may seem stranger still for an image from Siberia.

The photograph was one of many in a slide show at In Focus on autumnal beauty. Fall is my favorite season, and In Focus one of the best photography sites on the Web, but even so I was prepared to be underwhelmed. I expected to see the same images we always see at this time of year, the same colors, the same sameness. Perhaps this photo seems no different to you; harvest scenes are part of the repertoire and the transition into dormancy and quietude is part of the seasonal mood, so the conventions still are in place.

Consider, however, how the image sits a bit off center, like the hay bales in the photo. The mood is not so much autumnal as more profoundly liminal. Not so much fall in all its glory, but as if we are on the edge of winter, just as the field is on the edge of the lake. And is that deep, solid blue a fall color? It seems to be something out of time, almost as that lake seems out of place in the midst of a harvest scene. For these reasons and more, the photograph strikes me as more distinctive than many of the stock images of the season. And both more beautiful and somewhat unsettling for that.

So what is unsettling, beyond simply deviating a bit from convention? Let me suggest that this image is a masterful study of photography’s subtle deconstruction of spatial perception. Notice how the composition is a series of borders: the strip of snow in the foreground, the strip of field immediately beyond that, the rest of the field, the beach, the lake, the far beach, the strip of trees, the sweeping uplands, the mountains (or are they clouds?), the sky. . . . The visual expanse is a continuous succession of separate, parallel spaces, each of which becomes a border between two others. As they eye transverses from front to back along the empty center axis to the vanishing point, one might conclude that there is no there there. More to the point, the swaths of color and dabs of light seem to have been laid down on the flat surface of a canvas: the distance is but an illusion, a trick of the eye.

And yet we also see the sheer particularity of the pieces of hay sticking out of the two bales in the foreground. They are unquestionably near, while the other bales are far away. So it is that reality and illusion continue to interrupt one another. The same holds across the visual field of the photograph. Every place within the scene has a sense of extension yet also is interrupted by another; each one is unique and yet unable to either connect with or subordinate the others to create a sense of unity. Hence the comparison with Cezanne, as the material autonomy of each part of the work reveals an underlying sense of form, but one that refuses to channel a transcendental unity, leaving instead the specific weight of each part of the painting itself and with that its autonomy, a substitute for transcendence, as a work of art.

But it’s not a painting. And those bales and Lake Belyo are actually in Siberia, which is a very long way from where I am writing this post. Photographs are valued because of how they can bring distant views close at hand, and they are faulted for introducing unnecessary distance between the viewer and reality itself. Both reactions capture important elements of photography’s geographic capacity. This photograph fits either one perfectly: it has brought a distant scene into view, and it encourages aesthetic habits that could buffer my experience of the seasonal changes happening right outside my door. I may become accustomed to scenes that are empty in more ways than one, and yet I have been given a view of a beautiful world that extends far beyond the borders of my daily life.

Let me suggest that the photo takes us beyond this standoff. It suggest not only that any photograph is both far and near (and we knew that), but also that what matters are not the distances but the relationships. The image reflects the compositional processes that create photography’s internal space, with each photograph a virtual world in which space–and time–can expand and contract almost at will, but not to obliterate the distinctions that had been laid down in reality. Likewise, each photograph can be thought of as a liminal space: a threshold between two worlds, each of which in turn can lie between two others in a continuous succession of experiences, none dominating the other. Some appear to be near, others far away, but that may be the most complete illusion.

Photograph by Ilya Naymushin/Reuters.

0 Comments