Well, you tell me.

The short answer is San Francisco Bay. Or as the European Space Agency put it rather poetically, “An urban sprawl engulfs San Francisco Bay in a sea of lights.” The inversion of making the land mass a “sea” is a license we readily give to words, while pretending that our vision should be anchored more firmly to reality. According to the conventional wisdom, that anchor is supposed to be provided by the caption–the verbal description, which can be so easily or subtlely metaphoric, and you might want to think about that.

But I digress. The question remains whether you are seeing The Bay Area. Now that you’ve been told, perhaps, but could you pick it out of a lineup of other cities at night? Those who live there, sure, they might be able to zero in a bit as if on Google Maps, but most people would have to take it on faith.

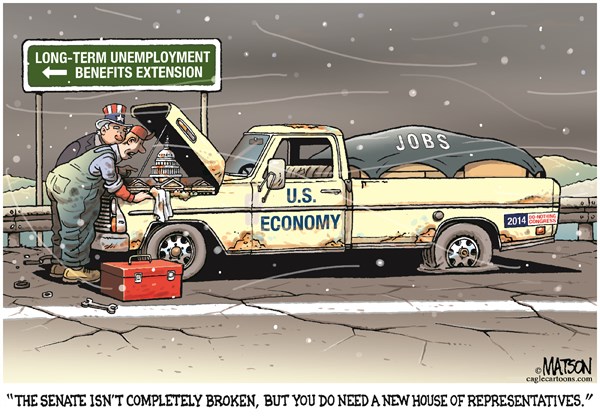

And so we do, and that may be a problem. Not the problem that usually is promoted at this point: I really don’t think there is an epistemological issue here. Yes, it could have been faked or there could be a mistake in labeling, but here as in many other places we can rely on institutional practices and social norms, not to mention the fact that most people have enough to do just telling the truth. (I fall into the latter category, so save your breath about me making it up.) It is what they say it is.

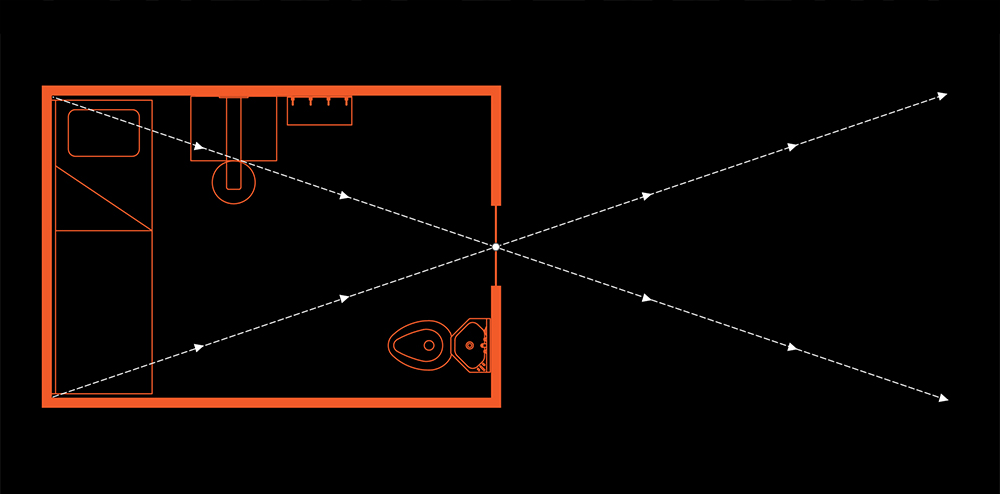

But is it? The problem I want to raise is that once you’ve been given a literal description of the image, your imagination may shut down too soon. The image is also an optic–a way of seeing–and we can think of the imagination as an extended way of seeing. Thus, any image might prompt imaginative extension, elaboration, or transformation of what is being shown, an extrapolation into the realm of metaphor, you might say. And why would one want to do that? Not merely to play with possibilities, although there is no law against that, but rather to get closer to what really is there to be seen.

Fortunately, the ESA caption wasn’t strictly literal. There’s another deviation in that regard beyond the “sea of lights.” We are seeing, we are told, “an urban sprawl” (my emphasis). That’s not standard American English usage, and so it opens a crack in the door of possibility. “Urban sprawl” would have been more typical, and it would have implied that we are seeing a general phenomenon, one that can be found and that would be much the same in other cities and countries. Such captioning is actually an exercise in abstraction, not direct reference to the hard ground of reality, and you might want to think about that as well.

“An urban sprawl” sounds more like a single thing–like an organism, for example. An amoeba. A virus. A radiant life form, a body electric humming with energy. Something that can pulsate, grow, replicate as it directs more and more energy through its neural pathways to become more intelligent, vital, beautiful.

And that can go dark in seconds, collapsing into a chaos of darkness as its energy disappears, systems crashing, gasping for the terawatts of power that no longer are available because the unseen earth has given up the last of its oil, coal, and gas. Or because another virus has emerged, this one too strong and predatory to be stopped, whether digital or biological, all that is needed to make the darkness sovereign.

Or perhaps something else. Pick your metaphor and try to see what the image is telling us. Think about it: it’s not really needed to do what governments do with visual technologies: surveying, surveillance, and propaganda could each be there, but weakly so, and they have far better options elsewhere. No, I think it’s provided because it’s beautiful and enigmatic, which is enough to intrigue and awe many people inside the space program and without. Best of all, it’s what you need if you want to see what really is there.

Photograph by ESA/NASA.

Cross-posted at BagNewsNotes.