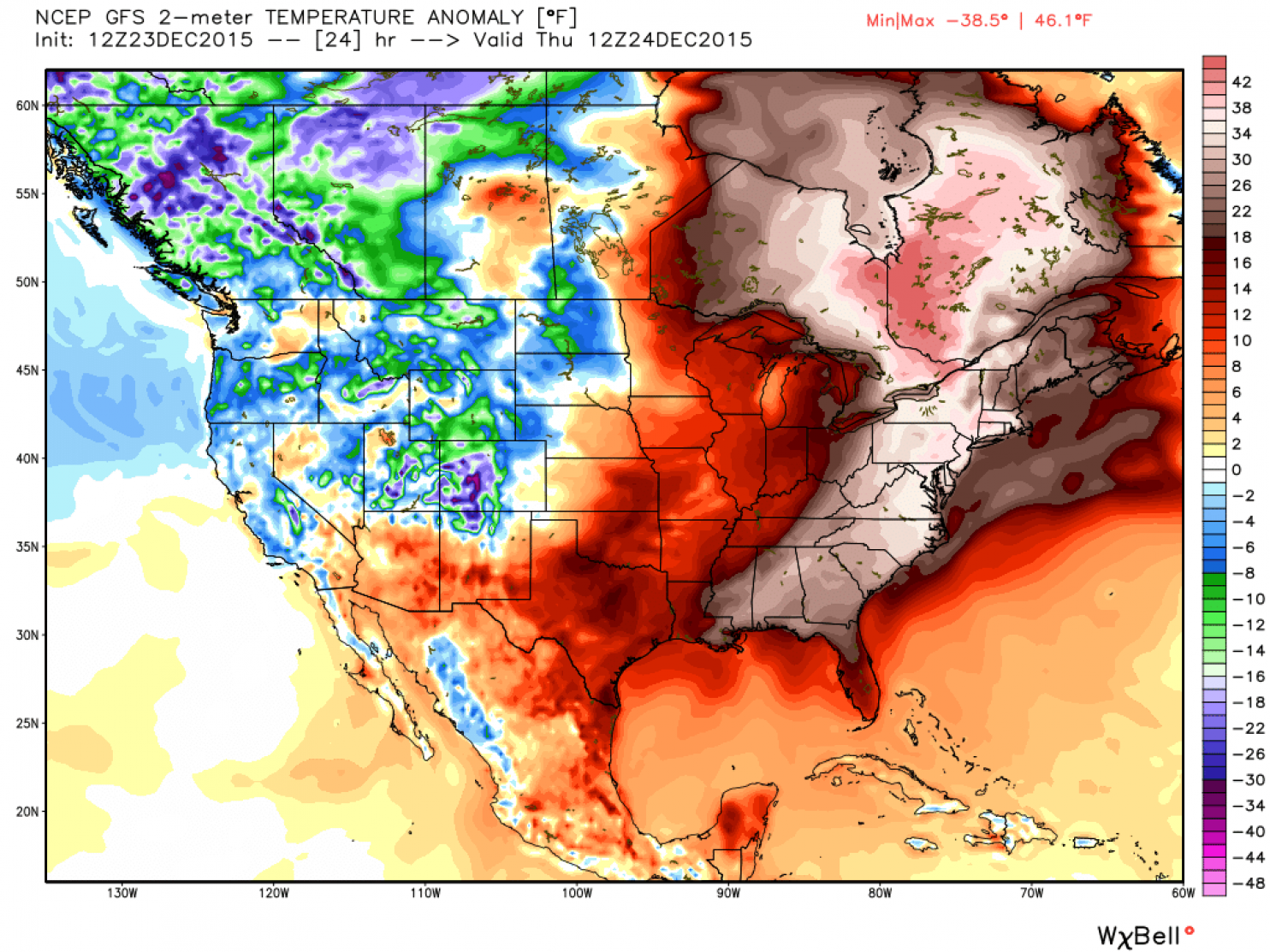

It’s only a projection from alarmist liberal media; nothing to worry about. (The map shows predictions for degrees above normal on December 25.) Enjoy the weather, and any respite you might find. NCN will be back in January.

Star Wars Optics and Socialist Dreams

Incredible, isn’t it? So perfectly designed and yet so strange. Ultramodern and yet medieval, like a space ship on a surveillance mission and a castle readied for battle, set off by itself in forbidding isolation and yet connected somehow to distant galaxies. The tableau is so unique and so striking that it could be a scene from the forthcoming Star Wars blockbluster: we can imagine the rebel stragglers, downed on an unknown planet, approaching the daunting edifice that has emerged out of the snowstorm. They can’t survive outside, but they don’t know what lies within. Friend or enemy? Life, death, or something worse than death?

They were socialists, actually: the structure is a monument to socialism built on Bulgaria’s Mount Buzludzha. It is one of a series of remarkable images captured by photographer Danila Tkachenko. The exhibition is available in the current issue of the National Geographic Magazine and at their website. Influenced by a nuclear waste explosion that had scarred his own family, Tkachenko set out “to look for other sites and structures that symbolized an abandoned march toward progress.” He found them.

The movie optic doesn’t come from Tkachenko, and I don’t intend to make light of his work. But science fiction movies and documentary photography have more and more important intersections than you might think. (Search for “science fiction” at this blog and you’ll see a few more examples of what I have in mind.) Tkachenko describes the now abandoned monument as a “very surrealistic object,” and he’s right. Although having the exceptional formal simplicity and coherence of a fine art object, it nonetheless is out of place with itself and its surroundings: the scene presents a mixture of aesthetics, politics, and an abstracted natural environment where each part seems alien to the others even as they fit together seamlessly. Surreal indeed.

Susan Sontag declared that “photography is the only art that is natively surreal.” That was not meant to be a compliment. It was instead a radical deconstruction of the medium that was thought to be inherently realistic. Sontag was right, but not in the manner that she would have wished. Photography is surreal, and good thing, too, for that is exactly why it is capable of capturing the “natively surreal” features of social reality. Which, I might add, is a lot of social reality.

The monument itself may not be to your taste. I think it is magnificent, but you might see a glorified birdbath. That disagreement is worth having, but it is beside the point today. The photograph has captured something more comprehensive than the artwork itself: the pervasive alienation of the socialist ideal on planet Earth. True, Bulgaria fell well short of the ideal society, and the money spent on the monument perhaps could have gone to help the common people rather than glorify an ideal or a regime ruling in its name. But if present trends continue, one can imagine a planet trapped in a perpetual winter of neoliberal capitalism. That planet could be dotted with massive, ultramodern castles surrounded by vast spaces of abandonment. It would seem like a movie to us today, but we already are living the trailer.

Perhaps an abandoned monument to a noble dream is surreal, but some day rebel stragglers may look up at the ruin and want to ask, compared to what?

Photograph by Danila Tkachenko. The quote from Sontag is from On Photography, p. 51.

Cross-posted at ReadingThePictures.

Security, Umbrellas, and Civil Society

The caption pointed to the soldiers on the Rue Neuve in Brussels, but what about the two figures on the right?

What about them? A couple walks under an umbrella; this is not news. No, it is not, but it does call to mind another European rainy day scene:

Gustave Caillebotte’s painting “Paris Street, Rainy Day” is one of the more remarkable depictions of the bourgeois civil society that made Paris the center of European modernity during the 19th century. The street scene is muted emotionally by the rain that has softened the brick surfaces of the city, while the couple’s comfortable domesticity under their umbrella becomes a small enclave of intimacy within the public space. Their easy entrainment contrasts with the empty spaces and isolated strangers behind them, and with the possible collision involving the stranger approaching them. He will adjust, of course, as will they, and so we can imagine a small ripple in the ongoing flow of urban civility–something to talk about when the couple is sitting at a cafe, but nothing more than that. And certainly not a terrorist attack.

I doubt that the photographer was thinking of Caillebotte’s work when snapping the photo in Brussels, but the connection in there in several ways. The contemporary couple could be inserted into the 1877 painting without much difficulty: they, too, are comfortably entrained while walking on the street on a rainy day, dressed for going out in public, enclosed in their private space beneath the umbrella, and contrasted with the strangers behind them and with the possible disturbance of an approaching figure who might step into their path. Although not in Paris, they are in a nearby European capital, and the photo is being taken because of what happened in Paris.

There also are differences, of course. Now she is holding the umbrella, which might be a small sign of gender equity. The scene behind them is a bit more crowded, and the dress codes have loosened up in the intervening years. Oh, yes, and there are four armed soldiers dominating the pictorial space. That’s not the Paris of 1877. We might want to call it the new normal.

If terrorists opened fire, you’d be damn glad those soldiers were there. Short of that, however, their presence is visually jarring, and should be seen as such. Masked, porcine, with multiple appendages, partially immobilized by their gear, suited for lethal conflict rather than civil association, they are visible proof that the civil society represented by the European city has been seriously disrupted.

Just as painting captured important features of 19th century modernity, photography may reveal characteristic truths about modern civil society in the 21st century. No photograph tells the whole story, and no painting does either. We also should acknowledge that 19th century Paris was aligned with an extensive expansion of European imperialism, and that the public life of the era was still gendered, raced, heteronormative, and otherwise well short of its Enlightenment promises. In like manner, more than one nation ought to admit that those attacking 21st century Paris are the issue of imperial histories, not least the Western entanglement with Saudi Arabia and an invasion and botched occupation of Iraq. Even so, both the painting and the photograph represent something essential about a decent civil society.

In the photograph, the couple on the right seems about to be edged out of the picture. Perhaps they will pass through without incident, but there may not be room next time. Instead of the openness evident in the painting, the civic space has become clotted with military force. If the enduring legacy of the attacks is to make a “security umbrella” an ever larger and more prominent part of urban experience, we may find that we have destroyed the city in the name of saving it.

Photograph by John Thys/AFP/Getty Images.

Cross-posted at Reading the Pictures.

Memorialization or Branding after the Paris Attacks?

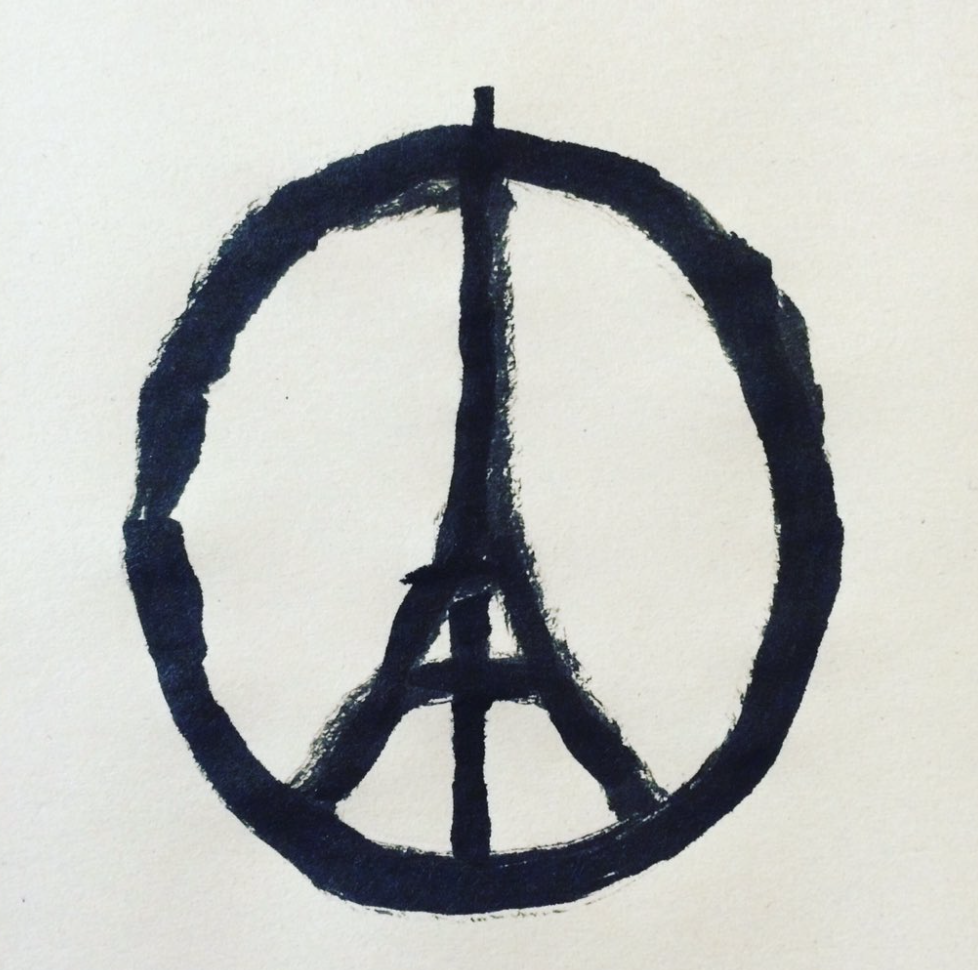

The drawing by by French graphic designer Jean Jullien has become one of the more widely shared artworks about the carnage in Paris. Like many of them, and like some of the photographs being shared, it includes the Eiffel Tower. Which is why the cynic might want to say that for all of the emergency claims being made, it’s still business as usual in the West.

To push the point, one might ask whether public opinion can ever get beyond tourism. (Susan Sontag argued that photography turned everyone into tourists, who were content to have only minimal knowledge and inauthentic relationships.) The outpouring of emotion far exceeded that spent on the ISIS bombing in Lebanon a day earlier or the ISIS destruction of a Russian airliner before that. I guess Beirut needs a tower, and the Russians need to paint Red Square on the side of their planes. The differences in coverage and response will depend primarily on powerful ethnocentric biases in the political and media systems, as well as the differences in the scale of the attacks, but one can’t help but think that the a lot still depends on the available symbolism.

That said, I think the critique is another example of how the cynic knows the price but not the value of things. The attacks were an assault on the city itself–and on its image as a beacon for living well in a modern civil society. Whatever the analysts might say about the political maneuvering of France in the Middle East, it was not the government buildings that were targeted. The city of light and love was attacked for what it was. What better way than the Eiffel Tower to communicate globally and instantaneously that we know and value what is at stake.

I think Jullien’s design is superb for other reasons as well. The Vietnam War era peace symbol has deep resonance for many of us, and it evokes two very important ideas: That once again a truly vile war is being waged, and that international solidarity is required to stop it.

Times have changed, of course: unlike North Vietnam, ISIS hasn’t a shred of legitimacy. But some things also stay the same: a string of unintended consequences has lead to disaster, and before this war is over many lives will be ruined for many years to come. More tellingly, the movement to stop ISIS can’t be only a peace movement, and those defending the West will have to also beware how war will transform their own societies. The effort to stop a ruthless tyranny also can lead to a national security state where the Paris of today is only a memory. The brand would continue, of course, but that really would be mere tokenism, like one of those miniature Towers that you can buy on the street.

And so the cynic might have a point after all, although not about branding. To defend Paris is to defend civil society as it is, with all its mashups of art, technology, commerce, politics, and everything else (including religion) that crazed ascetics would ban or segregate. But what about mashing up war and peace? The beauty of Jullian’s simple illustration is that it is a call for peace, and perhaps a claim that peace will triumph. It has arrived, however, just as France and other nations (including You Know Who across the pond) are gearing up for war.

Cross-posted at Reading the Pictures.

Generic Refugees and the World to Come

You don’t have to see too many of the many photographs of the European refugee crisis before they all begin to blend together. Even those that may seem moderately distinctive have a generic quality to them.

Was this photo taken in Croatia or Hungary or . . . ? In August or September or October? Are they from Syria or Turkey or Iraq? Headed to Germany or Sweden or wherever they can be taken in?

For the record, this photo is of Syrian refugees at a makeshift camp for asylum seekers near Roszke, southern Hungary, in September. For all I know, they’re still there.

One response to the generic representation of the refugees is to call for more contextualization. There is need for that, always, and both writers and photographers are laboring to provide more nuanced stories and images that can bring out the range of circumstances and experiences that make up the crisis. Let me suggest, however, that we also need to go in the other direction: the more interchangeable the images, they more they point toward the full significance of this historical moment.

The significance I have in mind was set out prophetically by Giorgio Agamben, who argued that refugees and other dispossessed persons were not exceptions to the modern political order of human rights protected by state institutions, but rather the representative figures of a dystopian world being produced by the continued development of modern forms of power. The real question then is not how or when will the more affluent nations absorb these migrants into their societies, but rather when will the citizens of those societies find that they have been reduced to the status of refugees?

Outlandish? Perhaps, and 1984 isn’t here yet either, so one could conclude that we have been warned and let it go at that. But plenty of photographers are not letting it go, whether they’ve read Agamben or not. Here I’m reprising an outstanding short essay by Anthony Downey in the Spring 2009 issue of Aperture. It should be required reading for anyone who is interested in the relationship between photojournalism and human rights. Downey takes up Agamben’s claim and turns it into an orientation for seeing what some of the images can show us about this critical moment in the self-understanding of modernity. Stated more simply, he suggests how photographers are already revealing a world in the making: one in which more and more people are being abandoned.

Downey’s essay is a brief one, so there is much that could be added, not least in counting all the ways of abandonment. Whether European states are unwilling or overwhelmed, and whether the conflicts producing the migrations fester because of political dysfunction or indifference in the global community of states is beside the point. At the end of the day, context may not have mattered so much after all. Especially if we we looking only for information, instead of asking how photography can disclose a world.

The photograph above may have a few clues to offer in that regard. Note how it already includes a surreal decontextualization of its own. We might start with the I (Heart) NY T-shirt in the foreground. Did he buy it in Times Square? (Could have, actually.) And the general mess of largely empty bedding is also disconcerting, as if the scene was somewhere between a teenager’s bedroom and the back room of a thrift store. And where is everybody, and how can we get a wider sense of things when our vision is so hemmed in by the plastic structure? Because the structure was built to be a greenhouse, one can even imagine that we are seeing a strange bio-political operation that produces bare life and cheap labor. These refugees are somewhere in the recent past and also somewhere in a possible future, while the present appears to be largely a mess. And not just any mess, but one that shows how people are already becoming habituated to abandonment.

If Agamben and Downey are right–and they definitely are not entirely wrong–then that NY T-shirt is also providing exactly the right context for viewing the image. That shirt can be found anywhere in the world, and so their world is our world. The migrations being produced by war and war-related disasters are another kind of globalism. One possible solution may involve a more cosmopolitan sense of political identity along with a low-impact economy of resource sharing, and the T-shirt, greenhouse, and other objects in the photo point in that direction, too. The crisis will continue, however, until enough people start to discern the possible worlds already being revealed.

We are all on the same road. Sooner or later, we will all belong to the same community. The only question is whether it will be one in which all but a few have been abandoned to a world of exploitation and displacement, or one in which hardship is shared for the benefit of all.

Photograph by Muhammed Muheisen/Associated Press. Downey’s article is “Threshholds of a Coming Community: Photography and Human Rights,” Aperture, Spring 2009, 36-43.

Cross-posted at Reading the Pictures.

Standing at the Edge of the Sea of Images

Wrong title, right? This strangely beautiful photograph is about the European refugee crisis; it is not about the contemporary media environment. True enough, but I’m asking it to do double duty.

After being in dry dock for five months, this blog is heading back to sea. The down time was used to finish our next book manuscript, and now The Public Image is in production at the University of Chicago Press. NCN started in the immediate aftermath of our last publication with the Press, and it has lead to another volume that we never anticipated writing at all. The book will be out in October 2016, and in the interim we will be posting here periodically. A redesign of the main page also is in the works, but as always speed will not be our strong suit.

We have noticed that photojournalism got along just fine during our absence. Good thing, too. We continue to be gratified at how journalism endures despite the wrenching technological and financial changes that are redefining the industry. This sustainability doesn’t happen by accident, and it requires everything from difficult business decisions to the personal obsessiveness of individual reporters and photographers. John and I are not part of that mix; we have another job to do.

This blog is provided to encourage the engaged spectatorship that is needed to make the most of photojournalism as it is an important public art for a democratic society. We focus on the individual image, despite the social fact that the audience is awash in a deluge of images cascading across multiple media and platforms. We emphasize the close relationship between aesthetics and politics, and not to warn against enthrallment but rather to understand what is being revealed about the world. We offer interpretations of specific images not to say they are better than others, but to suggest how every good image is inviting us into a liminal space between virtual and material worlds, involving past, present, and future realities, and offering important choices about how to live with others.

And so we get back to the photograph above. He, too, stands in a liminal space: between land and sea, the Middle East and Europe, life and death. His world is at once harsh and beautiful. Harsh because he can’t survive on either the cold sea or the hard shore, and the litter from previous refugees is a reminder that, although alone, he is part of a vast multitude that is severely straining the organizational and political capacity of the EU. He can expect only a hard road ahead, one where he may become even more vulnerable, more hungry, colder, and having bleaker prospects that he has at the moment.

For all that, however, he stands within a world of profound natural beauty. More important still, he adds to that beauty. His metallic blanket captures the silver tints in the sea and sky, and the flair of the blanket, now like a tunic made sea foam, evokes a long lineage of paintings and mythic figuration going back to Greek antiquity. Just as Athena, sea nymphs, a multitude of other figures, and before all of that our species came from the sea, once again something unexpected and uncannily human stands on the beach, standing between two worlds and sure to change this one.

And so the two strands come together. Whether any single viewer is there or not, photojournalism continues to provide a constant stream of images. Those images are the difference between living in a public world or being relegated to private spaces more or less subject to state control. Whether we look or not, the photographs are there, like a refugee wrapped in wind torn silver vulnerability at the water’s edge. Each image like each migrant is one of a multitude, but still one. Waiting for someone to say, “Here, come this way, we can find a place for you. Come to think of it, we might need to hear what you have to say.”

Photography by Aris Messinis/AFP/Getty Images.

NCN on the Road

John and I are hitting the road this week, and then one or the other or both of us will be away for many of the weeks between now and mid-September. During that time we also will be making the last changes on our forthcoming book manuscript, The Public Image, before sending it to the University of Chicago Press for the production work. We also hope to do a re-design of this website, to be rolled out in September, but that is well down the road at the moment. So–are you ready for the big disappointment–there will be no birthday post this year, even though our eighth birthday arrives in mid-June. That’s the age of the blog, not our mental or emotional ages, although some might wonder about that. In any case, we need the time off, and we plan to be back in the fall. If you are new to the blog, please feel welcome to browse around. There are over a 1000 posts in the archive, and should it be that our best work is behind us, that would be where you would find it.

Crossing the Border to the 21st Century

It is fitting that the first photograph of the 21st century includes an illegal immigrant.

Yes, scanner technology is there as well, and we’ll get to that, but let’s stop and consider what we are seeing. A stunning image, to be sure, but also one that mashes up a half-dozen critical transformations in the global environment, and yet doesn’t look like a mash-up. Because the photo has the autonomy of a work of art, it both prompts and resists interpretation. We see the patterns that already are transecting our lives to construct a titanium cage of biopolitical social organization, and yet we don’t see anything clearly. The gauzy colors and plastic emptiness of the scan are a parody of transparency, while the dark silhouette of the body blocks any identification above the primal level of embryonic species existence. The suitcase seems to be a womb; even the placenta is visible. The photograph itself seems to be floating in some larger womb, some larger context we can’t yet see but only feel all around us, as if the distant sounds of the world to come were reverberating through some invisible fluid.

It’s a boy, by the way. He was being smuggled into Ceuta, a Spanish territory on the coast of Morocco, on Thursday. He has a name (Abou), and a father who now is in custody, and we can hope that other family members can be located. But we already know that his situation is not exactly ideal. There are over 200 million migrants in the world, and you can bet that most of them are not medical doctors or engineers. Millions of people have to move across the globe simply to work, while those left behind struggle with all the problems that come from separation within the family and fraying of the social fabric within the community.

There are many photographs of migration, migrant labor, and the like (and see The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis, by T.J. Demos). This photograph, by showing less, shows more. We are not shown this or that immigrant and the typical circumstances and deprivations of the diaspora. Instead, the image points toward the global forces that are converging to make all labor migrant labor, and all of us illegal aliens.

The photo captures by turns the bare life of the human subject in migration; the emblematic equipment of global transportation and, with that, a powerful but harsh global economy that permeates everyday life; the vulnerable individual in neoliberal economic systems who has to be hidden and humiliated to acquire the means to live, and then is hidden and humiliated while working; the digital technologies for comprehensive surveillance of those subjects; the extent to which modern technologies that promised liberation can become cheap instruments of confinement; and not least, via the eerie suggestion of biomedical laboratory equipment, materials, and optics, the planned transformation of human nature. Indeed, one can imagine that the photo wasn’t taken for a human being, but rather for another machine.

So it is that a digital image from a government scanner of an illegal immigrant can become the first photo of the new century. The others of the past 15 years have been recording the passage of time, but this one has captured the brave new world that is forming, still largely in the darkness of a time we can’t yet see. A world, perhaps, where the post-human laborer already is being incubated.

Photograph by Spanish Gaurdia Civil/HO/Associated Press. A BBC report on the incident is here.

Cross-posted at BagNewsNotes.

Sight Gag: The “Unsinkable” American Self

Click on the above image. Then click on the image that appears.

Credit: Chris Jordan

Sight Gag is our weekly nod to the ironic, satiric, parodic, and carnivalesque performances that are an important part of a vibrant democratic public culture. These “gags” may not always be funny or represent a familiar point of view, but they attempt to cut through the lies, hypocrisy, shamelessness, stupidity, complacency, and other vices of democratic life. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think might deserve a laugh or at least a wry and rueful look by those who are thinking about the character of public life today.