In 1890 the immigrant social reformer Jacob Riis published How The Other Half Lives, a searing photo-textual expose of the appalling and inhumane living conditions of the 300,000+ residents packed into a square mile of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The Lower East Side (LES) consists of a number of neighborhoods, including Chinatown, Little Italy, the East Village, and most notoriously, New York’s version of skid row, the Bowery. And as is the case with many impoverished inner cities neighborhoods, the LES has undergone significant gentrification in recent years. So it is that the NYT recently reported on the renovation of The Prince Hotel, a nearly century-old flophouse located in the Bowery that continues to offer rooms—actually “cramped cubicles topped with chicken wire” —for $10 a night to a few men who continue to need a place to live and can actually afford the rent, but which also has converted several “upper” floors into a “stylish,” and “refined version of the gritty experience” for $62-$129 a night that includes “custom-made mattresses and high-end sheets. Their bathrooms have marble sinks and heated floors. Their towels are Ralph Lauren.”

There is something tawdry about the whole endeavor, to be sure. The real estate developers who came up with the idea of promoting a “flophouse aesthetic” believe that it embodies a “living history vibe” that is as much a museum experience as it is a hotel for “stylish young men and women.” Indeed, the NYT reports that the down-on-their luck individuals who live in the dilapidated cubicles on the lower floors are “an asset to the property,” apparently because they give some authenticity to the experience of “slumming”—a word, alas, which has returned to something like its original usage. We could go on at some length to criticize the industry of slum tourism which, at least until now, has been more prominent in developing nations like India, Brazil, and Indonesia than the U.S., but there is really a different and more important point worth making.

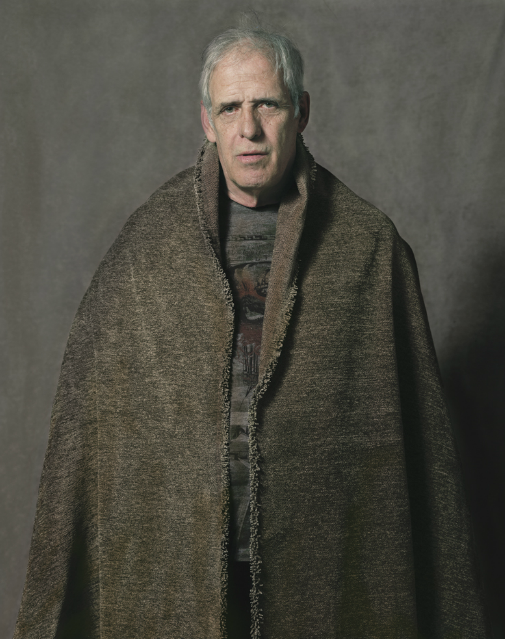

The two photographs above, which show one of the “nicer,” lower-level squalid rooms on the left and one of the upper-level, renovated versions of the “gritty experience” on the right invite us to see the direction of America’s economic future. Those who live in the room on the left have barely enough to get by (click here for a larger view). The room is dimly lit, and while neat and orderly, it is stuffed full with all of this person’s worldly goods. This is not the room of a destitute street person, after all, for they do have a television and other electronic equipment, including a jury-rigged ceiling fan, and they have enough money to pay the rent which implies some very minimal resources; but it is equally clear that their piece of the American Dream has eluded them. And a look at their bathroom facilities makes the point all the more. Those who live in the room on the right (here) seem to have arrived. They not only survive, but enjoy the luxuries of an aristocratic class, with designer towels and sheets, and black bathrobes (that apparently bear The Bowery House monogram: TBH). Their bathroom stands in marked contrast to those living on the floors below. The developer describes the clientele for rooms like this as “people who might choose a cheap cubicle for their city accommodations, yet go out for a $300-a-bottle table service.”

What we are given to see in these two images when put side by side (and by the hotel-museum aesthetic more generally) is a glimpse at a possible—and all too likely—economic future, a world divided between the haves and the have nots with little room in between. In short, we see a world in which the middle class itself has been erased. There are many reasons why this spells tragedy for our future—and somewhat ironically, not least the inability for a capitalist economy to sustain itself— but surely at the top of the list is the simple fact that a society defined by such stark and radical economic inequality will never be able to sustain a vibrant democratic political culture.

Photo Credit: James Estrin/New York Times.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.