Guest Correspondent: Bryan Thomas Walsh

It is campaign season again, that phase in the cycle of American political culture when candidates from both political parties stage over-the-top displays of patriotic grandeur: they salute flags, attend baseball games, eat hotdogs at state fairs or in corner diners, shake hands with the masses, and enact an array of additional public performances that are believed to enhance one’s public image. We are, in other words, moving from the circus of the Republican primaries to the carnival of the American presidential campaign.

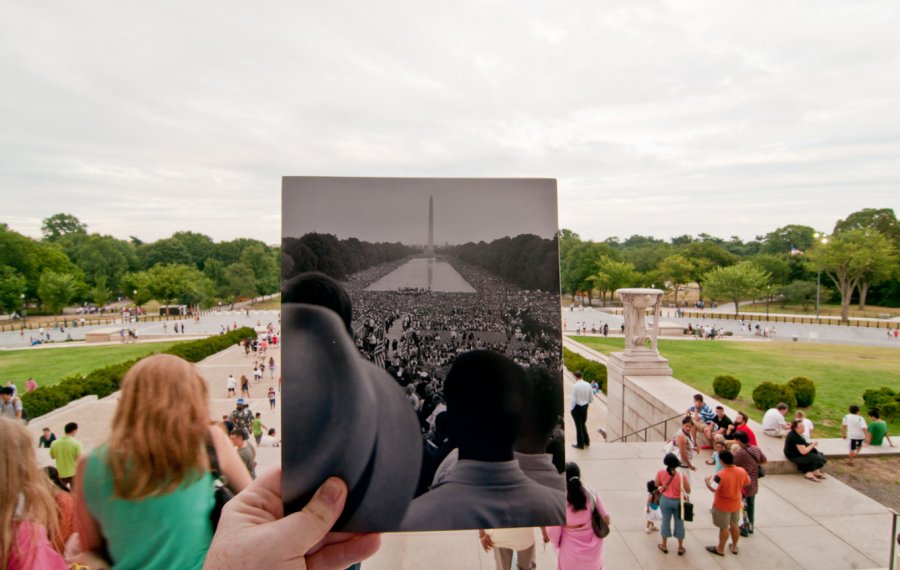

Given the ubiquity of hyperbolic theatrics that are so conventional to presidential campaigns, one might be taken aback by the above image. Taken just two weeks ago in Dearborn, Michigan by White House photographer, Pete Souza, the image captures President Barack Obama sitting solemnly inside of an empty, old-fashioned bus, looking intently out of the window and beyond the frame. At a glance, this is a puzzling image. Removed from the typical whirlwind of photographers, news reporters, and law enforcement, the President is seen here in a rare moment of solitude and private reflection. In many ways, the scene is neither spectacular nor conventional. It is only after reading the caption that we discover that the President is sitting in the very same bus where, almost 60 years prior, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man, thereby igniting the Montgomery Bus Boycott and reenergizing the Civil Rights Movement.

Of course, given the superficiality that characterizes contemporary campaign spectacles, it is not hard for viewers to read this image as a mere “photo-op.” Accordingly, viewers are invited to read the reference to Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement as an example of the President pandering to his liberal constituency and black voters in particular. Alternately, viewers can read this image as an attempt to frame the “first among equals” as an ordinary guy on his way to work, an image that Republican candidate Mitt Romney persistently fails to achieve. Michael Shaw at the BagNews argues that the image is an example of political “muscle-flexing,” where a crafty campaign strategy aimed at renewing the public’s opinions about the President parades around as a “candid photo involving a moment of deep reflection.”

While it is understandable for viewers to interpret this image within a cynical register, there remains something incredibly evocative and moving about the image. Indeed, the image emits an aura of authenticity – that is, it seems to capture a sincere and poignant moment where the President feels the gravity of the past and its bearing on the present or, more specifically, the role of Rosa Parks’ resistance to segregation and its relationship to the reality of Obama’s presidency. Rather than repeating the cliché and empty theatrics that saturate the campaign season, this image captures the President coming to terms with the fundamental fact that his presidency was made possible by those “second-class citizens” who defied a racist political system and executed acts of civil disobedience in hopes of realizing a more fair and equitable future for people of color. In short, the photograph serves as a history lesson insofar as it calls on viewers to recognize the role of civil rights struggles in having real effects (however oblique) on the vitality of present-day progressive politics.

But it is not only a history lesson; it is also lesson about social change. Seen here a year after the Montgomery Boycotts and the subsequent reintegration of the transportation system, Rosa Parks sits earnestly at the front of the bus alongside a visibly white passenger. The parallels between the image of Rosa Parks and the image of President Obama are striking: not only do both Parks and Obama occupy a space that was historically closed-off to blacks, but Obama unwittingly imitates the firm resolve suggested by Parks’ gaze. While the apparition of Rosa Parks reminds viewers that the Civil Rights Movement paved the way for a black man to serve as the President of the United States, she also reminds us that the vitality of contemporary democratic culture depends on the public dissent and civil disobedience of individuals and communities. One can only hope that Obama will take a hint from Rosa Parks – namely, that democratic promises are not always realized through compromises and civility; they emerge in the wake of overt and orchestrated political defiance.

Photo Credit: Pete Souza/White House; UPI/Library of Congress

Bryan Thomas Walsh is a Ph.d student of rhetoric and public culture in the Department of Communication and Culture, Indiana University. Correspondence should be sent to btwalsh@umail.iu.edu.

0 Comments