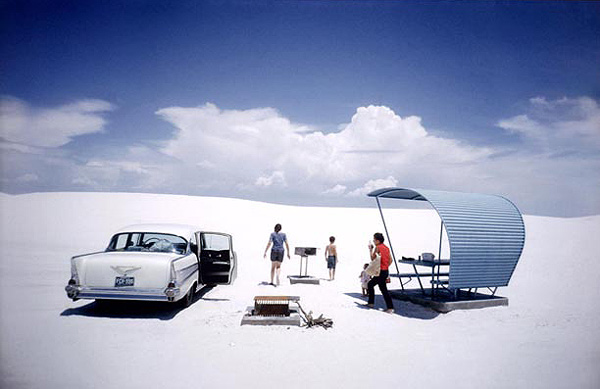

Sunday was Earth Day 2012, and I spent part of the day in my garden. If I had to live off of that garden, I’d die. Fortunately, environmentalism is well past the back-to-the-land movements of the 1960s (or was it the 70s?). Everyone recognizes that environmentally sound practices depend on complex networks of social interaction and economic interdependence. Of course, unsustainable use of the planet also depends on vast networks of production and distribution, so negotiations can be complicated. One way that humans deal with complicated realities is to turn to myth; a related option is to turn to art. Garry Winogrand did both at once in this photograph:

It was taken in 1964, and it is not your typical Earth Day image. Those who know the 1976 film, The Man Who Fell to Earth, might wonder whether the photo inspired the desert scenes on the plant Anthea, which was suffering from a catastrophic drought. Perhaps not, but the sci-fi reference seems apt anyway. Winogrand has brilliantly captured American cultural modernism at one of its most unworldly moments. Nor is the catastrophic implication entirely absent, as the photo was taken at the White Sands National Monument, which is not far from the White Sands missile range.

But I digress. Of all that is remarkable about this image, I am most captivated by the contrast between the comprehensively barren landscape and the sense of sublime possibility extending over the horizon. Instead of seeing the white desolation as the last place, the end of the line, a dead zone in which they could not possibly live, it has become instead a launch pad to another world. Everything is pointed or aligned toward the vanishing point, while mother and son are already walking forward as if entranced, caught up in something like the narcosis of the deep. The structure on the right could be a second vehicle, ready to hover and then glide through the desert air into the beckoning atmosphere. The image captures how modernism is always about the future–a mythic current that can carry people to the ends of the earth and beyond, but also one that can make any environment no more or less than a place for moving on. No matter how empty the place, no matter that one day a car will use up the last drop of gas on earth, the belief persists that humanity will keep moving forward, and that fuel-intensive technologies will have done no worse than to bring us to the point of transcendence.

Winogrand need not have thought of any of that when he took the photo, but his artistry nonetheless reveals how modernism is suffused with its own mythic yearning, an attitude that both motivates and rationalizes driving well past sustainable resource use. Of course, one must give complexity its due, as well as acknowledge how many benefits have come from moving beyond perceived limitations–benefits ranging from this computer to lifting millions out of perennial poverty. But other attitudes are needed as well, for prudential use of the planet will only come from balancing different perspectives.

Another artist is at work here. Andres Amador creates giant sand sculptures on beaches. Although it looks inked, he uses only a rake. The beautiful designs suggest a deep correspondence of art and nature, technique and flow united in the universal movements of earth, air, water, fire, planets and stars, seashells and galaxies. Not unlike scientific modernism, one might say, but with a difference. The painstakingly crafted design that you see was intentionally created during low tide. The artist labored knowing all the while that everything would be washed away, returning to the natural ebb and flow of the planet itself without human intervention.

There is Earth Day with all its good intentions and images of a better, greener life, and then there is the day after, when most people return to largely unabated, unsustainable consumption of non-renewable resources accompanied by toxic byproducts. The question is not how are we going to stop doing that today–our current practices were determined some time ago and we have next to no choice otherwise. No, the question is what is going to be done today and tomorrow that will shape what people are doing years from now. The answer may depend on facing what artists in varied media have revealed. One option is to see the arid plains and polluted waters as just another stepping off place to a dazzling future somewhere over the horizon. Another is to realize that everything will revert to nature eventually no matter what, such that beauty and longevity alike depend on what we do in the meantime.

Photographs by Garry Winogrand (Estate of Garry Winogrand and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco) and Andres Amador, Ocean Beach, San Fransisco.