The costs of war can be calculated in many different ways: dollars spent, resources depleted, opportunities lost, buildings and infrastructure destroyed, so-called “collateral damage” of all sorts, and of course lives erased. In the U.S. we often frame that last category in terms of physical death, and such loss is unquestionably the most tragic cost of war—and all the more so because it is borne so disproportionately by the nation’s youth, those who have the most to lose. Less noticed, though not entirely ignored, are the ways in which war impinges upon the psychic life of those who do the nation’s bidding and are otherwise cast in the national narrative as “war veterans.”

As a nation we have slowly and reluctantly acknowledged the all consuming effects—or should we say costs?—of PTSD and the epidemic of suicide among returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. But what we have a harder time recognizing are the ways in which those who fail to show the discernible symptoms of traumatic disorders nonetheless undergo a telling psychic transformation in the process. It may not be quite accurate to say that their lives are erased, but then again that might not be entirely off the mark either, as they no doubt come to face the world in ways, however understated, that bear little or no resonance with who they were before their experience as warriors.

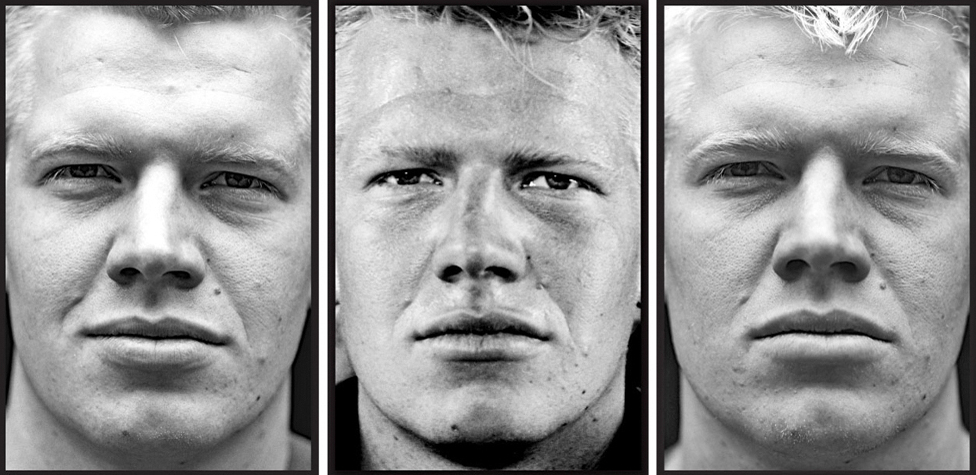

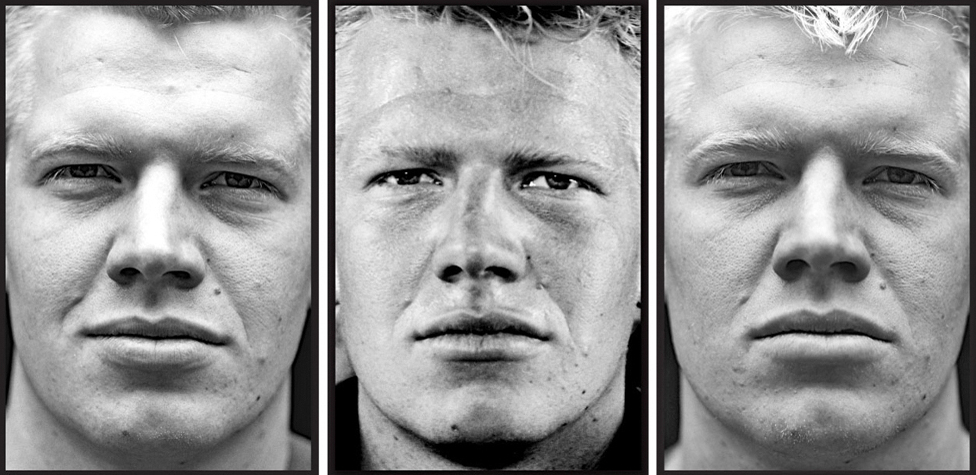

Claire Felicie, a Dutch photographer, has tackled the problem in a project called “Here are the Young Men.” Felice, the mother of a Dutch marine, photographed the members of the 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry Company of the Dutch Marine Corp five months before, three months into, and several months after their return from their deployment to Uruzgan, Afghanistan. Shot as tight close-ups of their faces in black and white and displayed as triptychs that mark time from left to right, the photographs invite the viewer to witness the subtle and yet often unnoticed changes in how these men come to “face” the world.

The photographs above are of twenty-one year old Arnold. At first glance it is difficult to identify any discernibly significant differences in the three portraits (which in a different context might be understood as mug shots), anyone of which might easily substitute for the others. But on close inspection it is not clear that we are looking at the same young man at all. The most noticeable features in each photograph are the mouth and the eyes. The photograph on the left displays a modicum of playful innocence. Note in particular the curl of his lips, slightly up on one side and down on the other, as if he is trying to look tough by avoiding the smile that lurks within. His cheeks have a youthful pudginess to them that ever so subtly direct attention to his eyes as they invite interaction with the viewer. It is a face that has yet to experience the world in any profound way.

In the middle photograph it is the eyes that dominate. Wide open, they seem to look past the viewer, not quite a thousand yard stare, but not far from it either. Note too the furrow in his brow that makes the rest of the face appear somewhat artificial, almost as if it were a mask that doesn’t quite fit the face it is attached to. And more, his cheeks are tight and gaunt, belying the youthful countenance of the first photograph, but more, suggesting a degree of caution, unsure of the world about him.

The final photograph is shot in a softer light that would ordinarily mitigate the aging process, but here it accents a face that appears to have aged too quickly. The set of the eyes is similar to the first picture, but rather than to invite interaction they intimate something more like cynicism. They don’t look past the viewer, as with the middle portrait, but neither do they signal anything like friendliness or trust. Not beady, as in the middle photograph, they nevertheless have an edge to them that invokes a steely coldness. The mouth underscores the affect, as it betrays no sense of being posed. The innocence of the first image is completely elided.

Taken as of a piece, the three portraits mark the subtle, psychic metamorphosis of a young man who has encountered the experience of war. The life he once lived has been inexorably erased, replaced by one that few of us who have not had the experience can ever know. Whether you find my reading of this triptych compelling or not, there is a different and more important point to be made, albeit one that is regularly ignored: the costs of war come in many forms, and too often some of the most profound costs are also the most difficult ones to see … unless we look very closely. We have Claire Felicie to thank for calling our attention to this insight.

Photo Credit: Claire Felicie

Crossposted at BAGnewsNotes

2 Comments