It seems that Greece has become the poster child for social democracy–except that the posters are being made by those who want to dismantle it. We Must Not Become Like Greece, conservative papers say as they preach the virtues of austerity. Of course, they don’t mean that we should beware profligate private sector investments and other dangers of global finance. No, no, the problems all stem from large public sector commitments backed by the foolish belief that government’s first priority should be providing for the general welfare. Instead, the road to prosperity should be one that separates winners and losers. Thus, Greece is being pushed to get on the right path, and it seems that the whole world is watching.

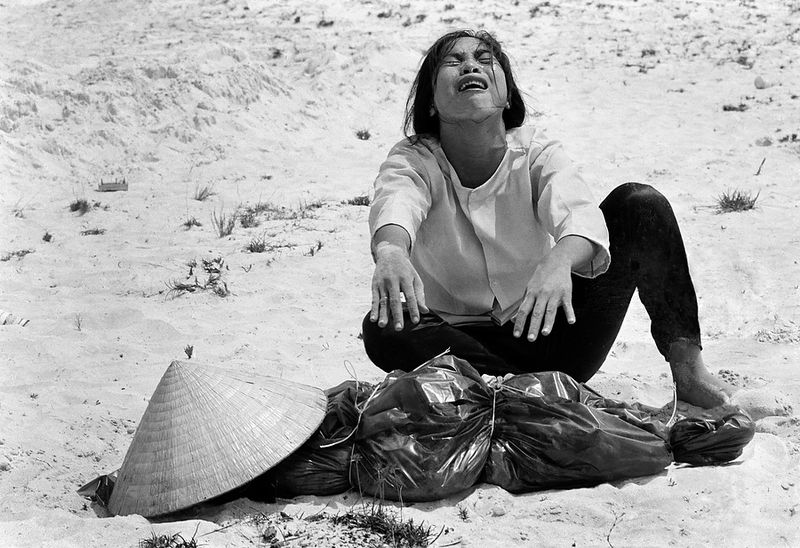

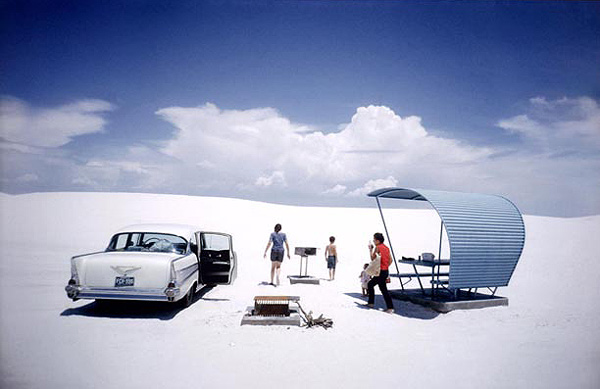

He walks along the street in Athens dutifully, a picture of anxious, unhappy resolution. The rumpled clothes don’t quite match the hard briefcase, as if he’s going back to the office on what should be his day off. He looks like austerity in motion: “I will work harder, damn it, I will work harder, and I will spend less.” Or is it, “If I work harder for fewer benefits, I might keep my job”? Or “If I try again, I might get a job, any job, maybe”? In any case, he is just passing through while the great, green eye stares impassively. Two public arts have fused perfectly here: the mural remains unchanged on the urban wall while the camera can capture how the space changes moment by moment. A man who might have seemed self-contained now appears to be small and vulnerable and perhaps disposable. An image that might have seemed idiosyncratic now can symbolize the terrible gaze of godlike global institutions.

A man tries to get through the day but now is weighted with an additional burden: he has become an object to be viewed, scrutinized, and judged. In that context, the mural’s Escape key is particularly troubling, as the otherwise human visage becomes at best a cyborg and more likely a soft illusion masking a hard technocratic regime. One might hit the button, perhaps even as an act of defiance, but all that does is reset the system, not destroy it, and it will blink on again just as relentlessly and devoid of compassion as before.

One eye mirrors another, just as camera mirrors computer, and so the viewer reproduces the gaze emanating from the wall. All eyes are on Greece. Caught in the glare of transparency, it is exposed to the full force of market logics. Enlisted as part of a neoliberal public demanding economization over all other values, the spectator is unwittingly complicit in an act of ritual humiliation at the alter of profit.

This is the first face of austerity: the face of the global financial system that stares and judges and punishes. It is all eye, a single instrument of enormous power, and one that can stare unblinking at the storm that we call progress. But there is another face as well.

This one is in Kalamatta. It is a face of pain and rage. These emotions have no one home, and so this image could be of the man’s enemy as it is about to devour him, or it could be ventriloquizing all that is pent up within him ready to explode as he is being beaten down by economic hardship. He could be merely thinking idle thoughts on a cigarette break, and unaware of how close he is to destruction; or he could be finally and willingly sinking down into that dark bright place where everything changes because there is nothing more to lose. Crouched as if waiting for the assault, his hoodie partially shrouding his face, he could be prey or predator. Either way, we are seeing the other face of austerity: the face of the suffering and violence that is its gift to the world.

Of course, Greece had problems enough of its own making–stagnation and cronyism not least among them–and some reform certainly is needed. But the artificial demands and phoney lessons now being promoted are more than simply mistaken and dangerous models for working out of the global recession. By demanding austerity, one can literally lose sight of what constitutes prosperity. As The Economist recently reported when surveying five decades of economic convergence: “In fact, most countries that were middle income in 1960 remained so in 2008 . . . Only 13 countries escaped this middle-income trap, becoming high-income economies in 2008 . . . One of these success stories, it should not be forgotten, was Greece.”

Whatever the face of austerity, it remains a very open question whether anyone is really seeing Greece: what it is, where it is, how it got there, and how it can continue to prosper. In fact, those questions could well be applied to any country. Unless economic policies are crafted with an eye to specific histories of successful public and private sector cooperation, and with concern for both global markets and local consequences, too many countries might end up wishing they were like Greece.

Photographs by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters and Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP-Getty Images.

1 Comment