This weekend the photojournalism community was flooded with debate regarding an exposé at BAGnewsNotes. The charges included deception and plagiarism and, in response, unprofessional reportage. Along the way, a number of people remarked that, aside from the specific case, the issues reverberated across wider circles of concern, from norms of photojournalism to the role and impact of new media forums to basic questions about the relationship between image and reality. When extended to this outer arc, one might want to encourage a more vital relationship between photojournalism and fine art photography.

“Artistic license” is, of course, nothing less than a license to fabricate, whether in stone, words, or images. It is for precisely this reason that photojournalists are trained to keep their work firmly grounded in recording what is, rather than fabricating what might be. Along the way, this discipline on behalf of the public interest can lead to a doctrinal hostility to artistry, and good photojournalists then become very skilled in an art whose name can’t be spoken.

The division of labor between documentary and fine art photography has many institutional forms, and is replicated in blogging as well: for example, one reason we do so little with fine art is that it is covered so well at Conscientious. But today is different.

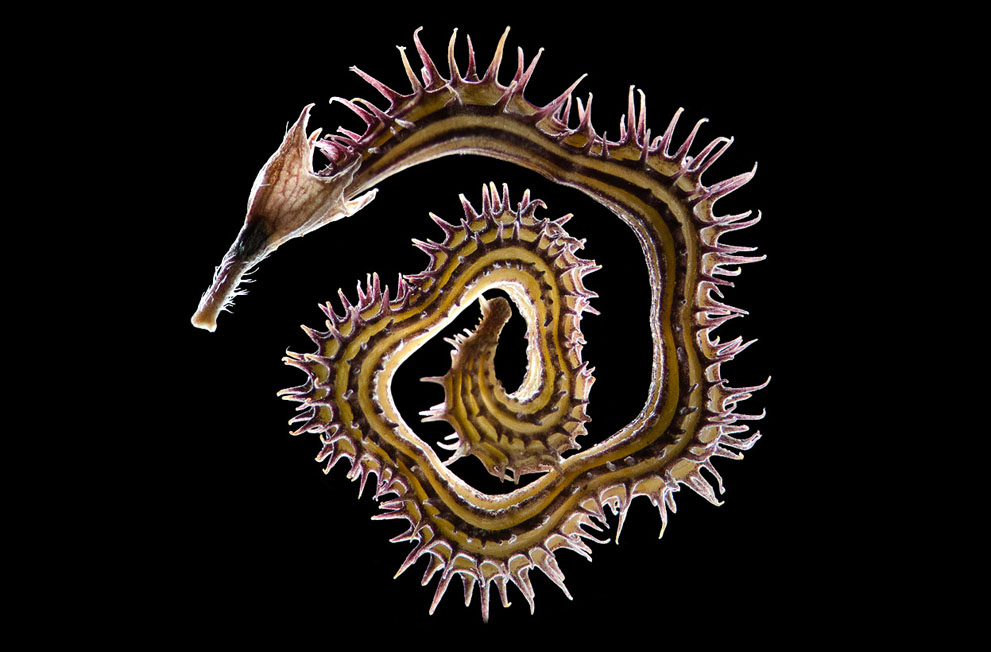

Is it a seahorse? A worm? Some small animal that may have inspired the image of a dragon? Or is it imitating some other organic form in order to hunt or escape predation? This beautiful image presents something that at once seems to be uniquely itself and yet also allusive, enigmatic, or evocative.

You are looking at a pod of the flowering legume Scorpius muricatus (common name “Prickly Caterpillar”). What might have seemed animal is vegetable. What might have seemed to be a parasite is part of a plant. What could have been an ornament from fantasy fiction or perhaps even some ancient culture is just a tiny fleck of nature.

But, of course, it is a fleck of nature that has been depicted artistically, framed for a special act of perception, capable of creating its own resonance with a much wider, deeper, richer sense of being. One can sense that animal and plants alike are all emanations of a beautiful, endless flow of form and energy. If there is any deception in the plant or its presentation or (most likely) in the mind of the spectator who can’t help but see several possibilities at once, this trick is in the service of opening the viewer to a profound sense of connectedness. Indeed, “deception” and the very idea of a hard discrimination between appearance and reality is no longer the appropriate framework for understanding. Sometimes that distinction matters a lot–it can be everything–but sometimes we can set it aside on behalf of other ways of being in the world.

The dissension and debate of public life is a very good thing, but we need repose and unity and wonder. And not just as individuals, but as a way of living together. Fortunately, photographers are providing the images that are needed for that as well.

Photograph by Viktor Sýkora.