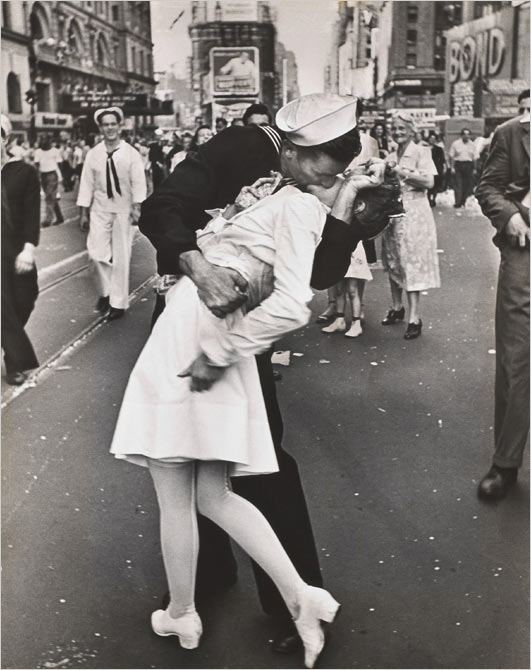

It is perhaps the most famous kiss in the annals of kisses. But the question has now been raised, is it more than just a kiss? And more, could it be an instance of sexual assault in full view of the public? There is much to suggest that, as it has typically been portrayed, the photograph is the representation of a joyous kiss celebrating the end of a war and the return to normalcy. And perhaps the most important evidence here is the reaction of the members of the public who look upon the heterosexual kissers approvingly, smiling rather in the way we might imagine an older generation’s response to the exuberance of young love.

But there are also reasons for concern. The sailor is clearly the aggressor and the nurse is clearly passive. Take note of the fact that she is not returning his embrace. Indeed, from one perspective, at least, she appears to have gone limp, succumbing but hardly complicit. And then there is this: The most recent woman to be identified as the nurse, Greta Zimmer Friedman, reports that “[i]t wasn’t my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and grabbed!” And more, “I did not see him approaching, and before I knew it, I was in his vice grip [sic].” And then this, “That man was very strong. I wasn’t kissing him. He was kissing me.” If this were to be reported today it is pretty clear that we would judge the sailor’s behavior as more than just inappropriate but as a sexual assault. The question seems to be, should we impose contemporary norms on what we might imagine as a somewhat distant culture? The answer is not obvious.

Perhaps we should begin with some context. Everyone remembers the photograph as an icon of VE Day. What most forget is that it was one of a series of images in a Life magazine photo essay titled “The Men of War Kiss From Coast to Coast,” and more to the point it was the last image in the array and the only one to occupy a full page. To a number all of the other photographs depict lascivious if not downright transgressive public acts (here, here and here). But, and here is the point, in almost every instance, the women appear to be—or are described in the captions—as being complicit. When we turn to the “Times Square Kiss” in this context we see something that seems to be the model of restraint: two kissers lost in passion even as they enact the decorum that is the necessary discipline of public life. We hardly attend to the original caption that notes, “an uninhibited sailor [who] plants his lips squarely on hers.” It was clearly a different time. As one soldier from the “Greatest Generation” was quoted in the Saturday Evening Post in 1944, among the things we fight for is “the priceless privilege of making love to American women.” And in their own way, this full array of Life photographs makes the point.

And yet there is something altogether dissatisfying with leaving it at that. And not just because times have changed. Ariella Azoulay has recently asked, “Has anyone ever seen a photograph of a rape?” Her point is not that such photographs do not exist – they do, however rare. Nor is it that they are not available for viewing – they are, although again their circulation is rather limited. Rather, her point is that even as we have reconstituted our notion of rape since the 1970s in ways that liberalizes the meaning of sexual assault and underscores the responsibility of the state to protect women, it continues to be an invisible object in the public discourse, an image that we proscribe from showing and, more importantly, fail to see even when it is before our eyes.

The real challenge here then is not so much to critique the blind sexism of an earlier moment in our history, however much it might be mischaracterized as a golden past, but to question why we continue to refuse to see what might now be before our eyes. Put differently, the question is not what does this photograph tell us about our past, but rather what does our refusal to see the photograph in the context of Greta Zimmer Friedman’s memory of that day tell us about our present.

Photo Credit: “VJ Day in Times Square, August 14, 1945,” by Alfred Eisenstaedt, © Time Inc.

We have previously written about this photograph on this blog (here, here, here, here, here, here, and here) and in print (here and here).

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.