Much of what we experience as war photography focuses attention on the manner in which war is fought. And whether the photographs we see shows soldiers conducting military campaigns, interacting with local children in occupied territories, experiencing the boredom of war that punctuates the time between skirmishes, suffering from wounds both physical and psychological, or returning home to the hugs and relief of friends and families—or worse, in flag drapped coffins, the focus is always on what we might call “the conduct of war.” And because wars are typically fought in the name of collectivities the role of the individual is played down—not erased entirely, but nevertheless minimized, as such photographs underscore the archetypal quality of the scenes displayed. Individuals tend to stand in for something larger than themselves. And yet for all of that, one of the genres of war photography continues to be the individual portrait.

The most common portraits of soldiers tend to be taken prior to battle and usually feature the soldier in full uniform. This is of course a practice that is as old as the Civil War. And whether taken by the military itself or by friends and family members, such portraits veil the identity of the individual beneath the uniform and mark the soldier first and foremost as a representative of the nation-state. In recent years a number of photographers have begun to challenge such work and in a ways designed to remind us of the individuals doing the fighting (here and here). Among such work is the photography of Suzanne Opton.

In a series of projects beginning as early as 2003 Suzanne Opton has been photographing individual soldiers, emphasizing the artistic conventions of portraiture designed to help us engage and understand the individual qua individual. And with stunning results. Taken “at home,” rather than on the war front, the soldiers she photographs are all out of uniform. And thus there is a sense in which their status as “citizen” is accented, rather than their status as “warrior.” And yet at the same time they are unmistakably marked by their experiences as warriors.

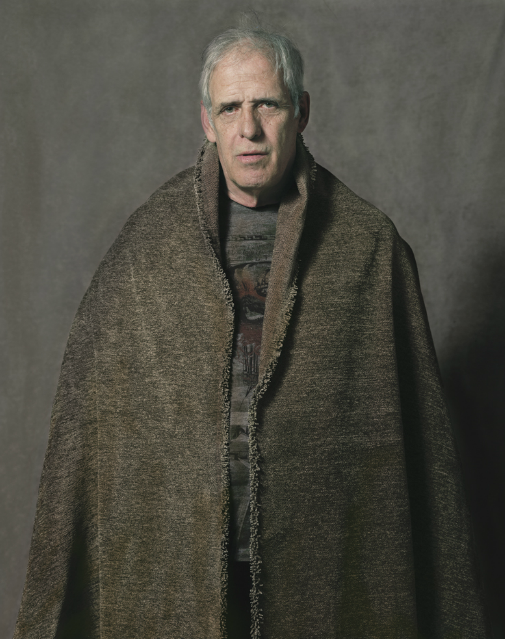

In one set of images, titled “Many Wars” she photographs veterans in treatment for combat trauma, but what marks the series is that they cut across every American war from World War II to the present. As with the photograph above, they are shrouded in cloth, and generally distinguished by age, though only somewhat incidentally by the particular wars in which they fought. And the point seems to be that we need to see them as one, even as they are portrayed as individuals—a paradox that underscores the in/visibility of war as it crosses generations (and more).

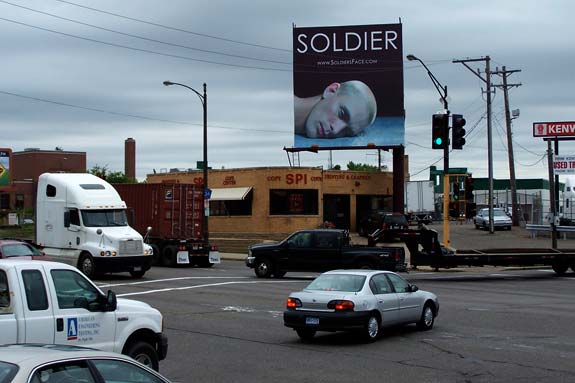

In one of her most recent works, titled “Soldiers” she photographs veterans returning from Iraq, by asking them to lie on the ground with their faces at rest, almost as if they were preparing to go to sleep. The pose not only resists the typical conventions of portraiture (showing the individual sitting or standing up straight, shoulders back, emphasizing their strength and agency) but locates them in that liminal state between full and active consciousness and the dream world of sleep. The pose surely operates as a visual metaphor for the condition of such individuals. There is also a gesture here to the “two thousand yard stare” that recurs as a convention of war photography, made all the more haunting by the fact that these individuals are out of uniform and thus that much closer to us as citizens on the home front. These photographs were part of a provocative and controversial “Billboard” campaign which, in their own way, demonstrate the sense in which the soldier has become more or less in/visible.

Whatever one makes of Opton’s work, it is clear that she is challenging us to think about the conventional representations of war and the warrior-citizen, and more, the implications for how we experience and engage such representations as we go about our daily lives. Suzanne Opton will be lecturing on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington, IN on Monday, October 3, 2010. The title of her presentation is “Many Wars: The Difficulty of Home” and it will take place in Fine Arts 015 from 7:00-8:30. If you are in the neighborhood I encourage you to attend.

Photo Credits: Suzanne Opton

Note: My colleague Jon Simons and I are co-hosting the 2011-2012 Remak New Knowledge Seminar on “The In/Visiblity of America’s 21st Century Wars.” As part of the seminar we will be bringing eight speakes to campus including Michael Shapiro, Roger Stahl, Diane Rubenstein, Nina Berman, David Campbell, Wendy Kozol, and James Der Derian. Suzanne Opton is the first speaker in the series. In April 2012 we will be hosting a conference on the same theme that will include presentations by Robert Hariman and Michael Shaw.