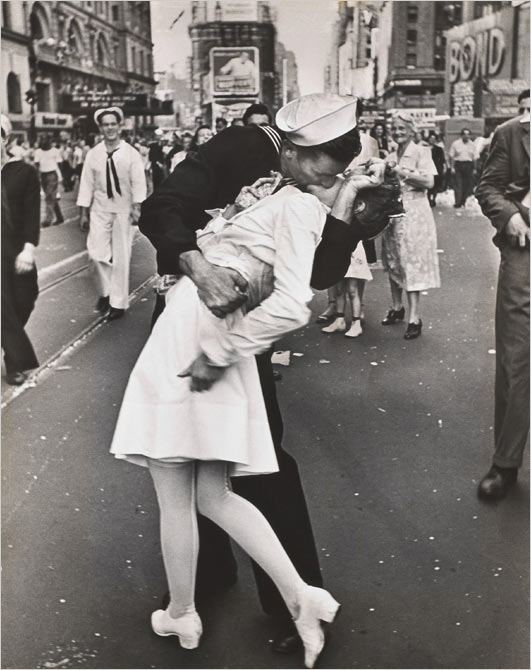

Two lovers caught in a passionate embrace. He on the left, she on the right. Their faces barely recognizable as their bodies meld into one another. Oblivious to all that surrounds them, it is a tender, private, intimate moment in a public space.

At first blush it could be two individuals (once again) performing the now famous Times Square Kiss in a modern setting. But look again. The differences are both subtle and profound. Neither is wearing a recognizable uniform. She is actively engaged in the kiss, her arms pulling him towards her as much as (if indeed not more than) he is pulling her towards him. Notice for example how his right arm seems barely to be holding her while her arms reach fully around him, holding him in place. More interesting still is the fact that she is holding a slab of concrete in one hand, her finger nails giving the impression of being freshly manicured. If the sign of the kiss in the original photograph was animated by an aggressive, masculine representation of state military power, here the kiss is no less a sign of aggression—it is hard to imagine that the concrete slab would be used as anything other than a weapon, particularly given that the caption tells us that this is taken at the site of a protest—but it is now no longer institutionalized by the state and it is gendered feminine. Last, and perhaps most important, while the kissers are plainly and visibly in a public space, there are no onlookers who can channel a public attitude about what is going on. Indeed, there is a clear sense of voyeurism here as we, the viewers, seem to be intruding on an altogether private moment.

So what are we to make of this photograph? The caption identifies the kissers as protestors in Caracas, Venezuela, the site of prolonged and massive public protests against rampant crime, protracted food shortages, and an altogether ineffective and authoritarian government. The government crackdown against such protests has resulted in nearly forty deaths and hundreds of injuries, leading to demands for investigation by the Organization of American States (OAS). That too has produced its own manner of controversy as the OAS leadership challenged the legitimacy of opposition leader Maria Corina Machado to address the body. When she was finally allowed to speak, the sessions were held behind closed doors; one member of the OAS noted that the meetings would be conducted “With total transparency: In privacy.” The photograph above seems to mock this “war is peace, slavery is freedom” logic as it failingly purports to perform intimacy in a public space under the broken veil of privacy. There may be no viewing public observable to legitimize the union, but then of course there is the camera and our own spectatorial gaze which gives the lie to the whole process. Transparency in private is at best a comfortable fiction and at worst an intentional deception.

There is an additional dimension to the photograph that bears attention, and it has relatively little to do per se with the economic and political turmoil in Venezuela. Instead, it concerns how we understand Alfred Eisenstadt’s Times Square Kiss and all it stands for in our cultural memory. The original kiss photograph took place on the occasion of VJ Day and the end of World War II. It is often remarked as illustrating the return to normalcy. But its contrast with the image above helps to reveal how constructed the conventions of such normalcy can be: men kissing women, women being kissed; the legitimation of violence as a manifestation of masculine, state governed military institutions; the forced separation of Eros and Thanatos; the performance of intimacy in public, and so on. All such constructions—or should we call them “comfortable fictions”— indicate a particular worldview, to be sure, and perhaps even one that we might want to endorse, but the point is that it is particular, not universal. Each photograph shows “a” truth, or many such truths, but certainly not “the” truth, however objective the photographic representation of the event on hand might be.

As the song says, a kiss is just a kiss … or is it?

Photo Credit: Christian Veron/Reuters