Homelessness in the United States persists. Estimates vary, but by most conservative accounts 3.5 million people experience homeless each year. That said, it is only a mere 1% of the population. And the number has actually declined a small bit in the past few years. No problem, right?

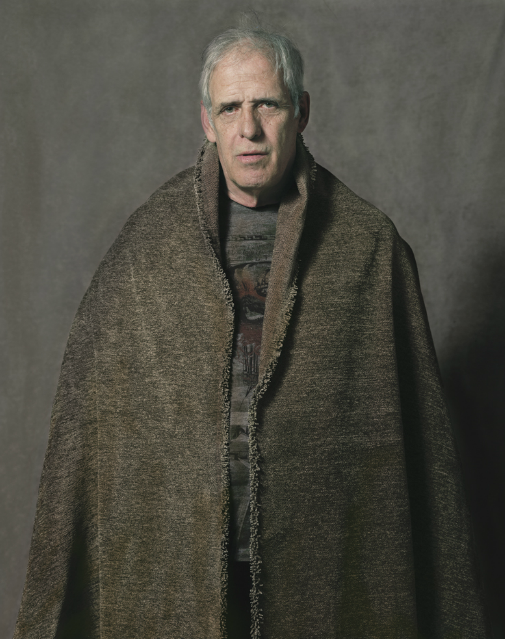

But consider this: 35% are families with children, 25% are under the age of 18, 23% are military veterans, 30% have been the victims of domestic violence, and, no surprise here, 25% suffer from some form of mental illness. The problem is significant, in other words, and many of the most vulnerable are in little position to do anything to help themselves. And so the socially conscious continue to pursue awareness campaigns.

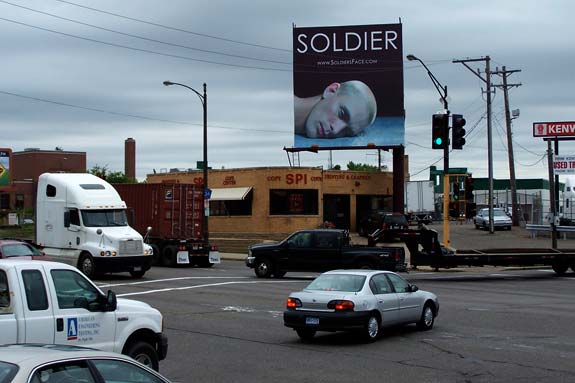

The photograph above is from Cape Cod, MA, where 27 high school students “slept in cardboard boxes and took turns playing in a 10-hour continuous soccer game throughout the night.” The effort is well-intentioned and even honorable, but the question is: what do we see? Or perhaps, more to the point, what are we being shown? Not the homeless—or their condition—that’s for sure.

There is something of an irony here. At its heart, a huge part of the problem with homelessness is that it is a human condition that we are conditioned not to see; indeed, it is a social phenomenon that we actively turn our head away from: as children we are told not to stare and as adults we look through the homeless on our streets as if they were altogether invisible. And so, of course, the need for awareness. But there’s the rub: As much as we seem to try to animate awareness we do it by turning attention away from the thing itself and to those who no doubt feel righteous in their service to a larger cause. And as with this photograph we complicate the problem further by substituting faux homelessness for the real thing.

Look closely at the photograph. Those sleeping “in cardboard boxes” is a bit of a misnomer. They look more like children who have constructed a play fort in their living room or basement more than anything approximating a homeless person consigned to sleeping in a tattered and used cardboard box. They all look well fed. While they are surrounded by a wall of cardboard they are actually sleeping in what look to be clean and warm sleeping bags with more pillows than they know what to do with; comfortable and content, they rest with their faces fully exposed to the world as if without a care in the world. And why not. After all, they are not exposed to the elements. There is no rain or snow or cold to contend with and the bright lights of the gymnasium add an extra level of security that those sleeping in parks or alleys or under highway by-passes and bridges can rarely if ever rely upon. Those not sleeping are playing soccer, another sign that all is safe and secure. And, of course, when morning comes they will return to their homes—no longer homeless!—where breakfast and their own warm beds await.

So again, what are we being shown? The all too easy answer is the efforts of young people working to right a social wrong the best way that they know how. And the photograph certainly does that. But more than that it also shows how easy it is to sentimentalize a profound and complex social condition, to invoke the pathos necessary to action—and for that matter to access our very humanity—and at the same time to contain and direct such emotions away from the actual problem itself. Instead of seeing the homeless and the common problem that it poses for a liberal democratic society, once again we are encouraged to look elsewhere.

Credit: Stan Grossfeld/Boston Globe Staff