Whatever your politics, you’ve got to be affected by this photograph of the aftermath of a suicide bombing in Maimanah, Afghanistan.

Even if viewed by an Afghan citizen opposed to the US occupation, I think the image would be mesmerizing. It has a magnetic pull something like what happens when traffic slows to a crawl as it passes by a really bad roadside accident.

The two soldiers are survivors, it seems, but even they are stunned and slowly dropping into an immobility and isolation approaching death. Behind them, someone worse off is being dragged unceremoniously away, whether to a hospital or the morgue remains unclear. The empty space in the middle of the frame seems to radiate out from the pole, as if reverberating from the blast that already has occurred. Weapons and body armor are scattered on the ground, or slung over the back of one of the police officers, so this is not a story of projecting power, building stability, or any other imperial objective. This miniature battle was over as soon as it began, and all that remains is the frenetic running around of some Keystone Cops doing damage control.

The fact that three people in the scene are taking pictures only adds to the sense of chaotic futility. Shoot all you want–and a lot of good that will do the guys on the ground. Pan further into the background and you’ll see that for other spectators it’s a lot like driving by a really bad accident.

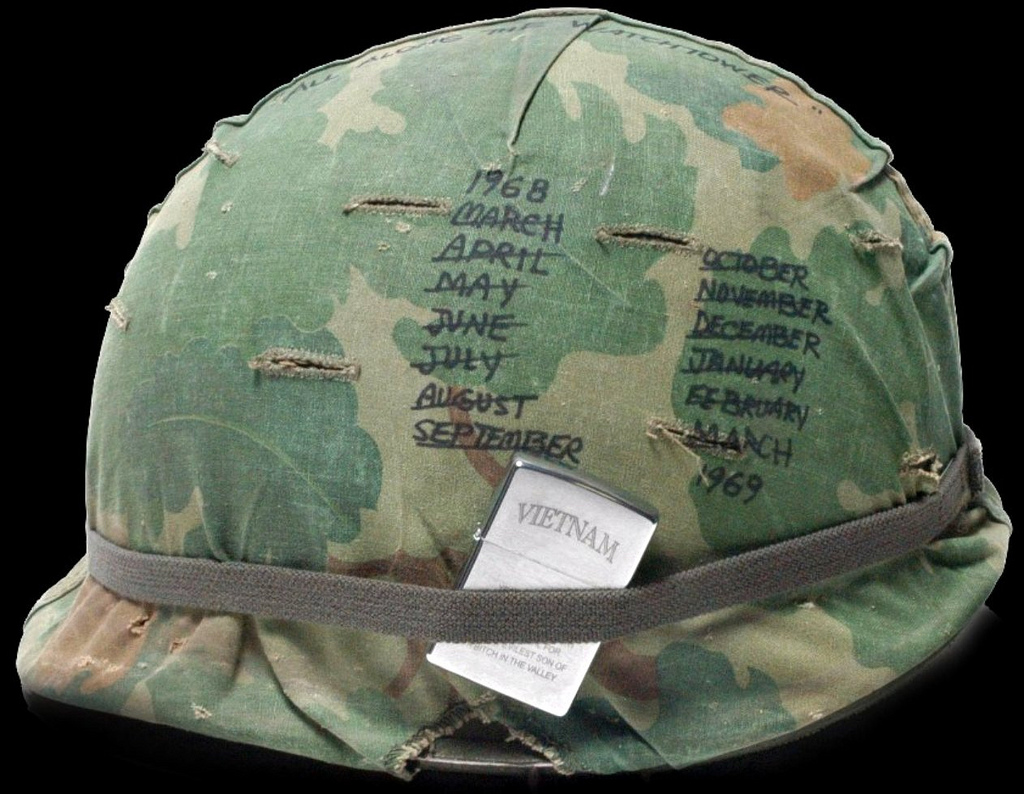

The photograph was taken in April. Not this month, and so it’s now being taken somewhat out of context. Or is it? April, May, last year, this year, does it really matter to most people? Ten years and counting, “context” starts to sound hollow–what kind of context is appropriate when images become interchangeable and few are paying attention anyway? And even if I supplied the rest of the captioning information–April 4, 2012, at least ten dead, etc.–would that create anything like the terrible body blow that knocked those soldiers to the ground?

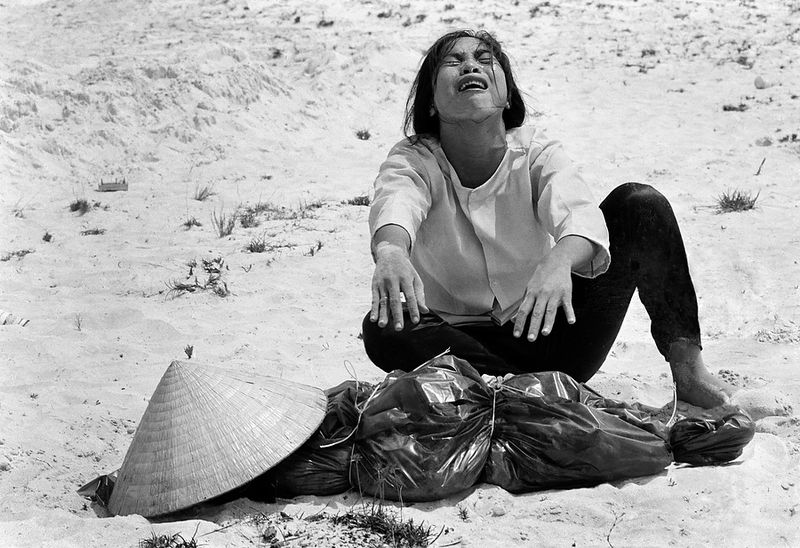

Contextualization is one of the most important ways of articulating and anchoring meaning, but there also are important ways of thinking that become available through decontextualization. By letting the image resonate while withdrawing those props that can be used to place, categorize, rationalize, and file away the event, one may, however briefly, be awakened to empathy and thus to serious thought.

Thinking includes comparisons, and another benefit of taking things out of context–which we do all the time when using language, by the way–is that one can make unexpected comparisons. Like this one, for example.

One picture or two? Well, two. In the second image the man down is a civilian and his assailants are right there rather that vaporized. He isn’t so much knocked into semi-consciousness as struggling painfully to avoid being choked and smashed into the pavement. And the cops are attacking, not scurrying about, and hurting rather than helping. In fact, they are all citizens of the same country, though not on the same side. The photo is of violence occurring at a Labor Day march in Santiago, Chile, which is a long way from Afghanistan.

But not as far as you might think. This photo, too, could have been taken in many another month or year. Indeed, the neo-medieval body armor of the riot police suggests that the scene may be more timeless than we know. And one of the more punishing side-effects of globalization is that the world is coming to have one continuous street. And that street is the scene for insistent outbreaks of dissent, protest, and other forms of resistance, and for recurrent crackdowns by security forces having varied uniforms and insignia but an increasingly unified apparatus of equipment, techniques, training, and deployment. And one way or another, it seems that the guys getting knocked down are being betrayed by leaders too complicit with the redistribution of resources up the economic hierarchy. It’s all one street and sometimes it seems to be all one war.

So perhaps they are similar images after all. In a world becoming re-habituated to violence, the usual distinctions come to mean less and less. In order to comprehend a world out of joint, sometimes the photos have to be seen out of context.

Photographs by Gul Buddin Elham/Associated Press and Luis Vargas/ZUMAPRESS.com.